In 1945, 75 years ago, World War II in the Pacific ended with the Battle of Okinawa and the atomic bombing of Japan. These important events, in which Wisconsin service members did their full duty, still impact the world today.

From April until August 2020, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum staff will explore World War II’s end, highlighting materials and stories of Wisconsin veterans in our collection. Follow the links in the post to explore related collections and more Wisconsin stories.

WVM.1023.I087.01

Okinawa: Genesis of a Battle

The Battle of Okinawa, which raged from April 1st to July 2nd, 1945, was a remarkable struggle in many respects. It was the final battle of World War II in the Pacific, the last major battle before the atomic age, and the largest sea-air-land battle in history. It also cost more American casualties than any previous Pacific battle.

The invasion of Okinawa and the surrounding Ryukyu Islands, codenamed ICEBERG, resulted from strategy decisions of the previous summer. After the invasion of the Mariana Islands in June and July, 1944, U.S. forces stood ready to push into the Western Pacific toward Formosa (modern Taiwan) and the Philippines. Planners in Washington favored Formosa as the next target, while General Douglas MacArthur pushed for going to the Philippines. After considerable debate, the decision was made to liberate the Philippines. Admiral Chester Nimitz, commander of the Central Pacific forces, would bypass Formosa and seize key airfields and bases in Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Victory in all three places would set the stage for the climactic invasion of Japan proper.

The capture of Okinawa was assigned to Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner Jr.’s Tenth Army. Buckner commanded 183,000 soldiers and Marines, divided into Marine Major General Roy Geiger’s III Amphibious Corps (1st and 6th Marine Divisions) and the Army’s XXIV Corps (7th, 27th, 77th, and 96th Infantry Divisions) under Major General John Hodge. Offshore, over 1,000 British and U.S. ships of Admiral Raymond Spruance’s Fifth Fleet would support Buckner’s forces.

Defending the island were the 100,000 Japanese soldiers of Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima’s 32d Army. The defenders included veterans of fighting in China, reinforcements from Manchuria and Japan proper, and over 20,000 Okinawan volunteers. Naval and air units in Japan also stood ready to assist the defenders.

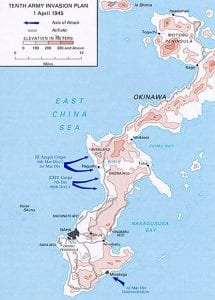

Tenth Army Invasion Plan

Both Buckner and Ushijima developed plans that accounted for Okinawa’s geography. The island was long and narrow, measuring sixty-two miles long and two miles wide at its narrowest point, and hilly in its northern and southern ends. Most of the population lived in the island’s southern third, which was also the site of Naha, Okinawa’s capital and best port.

Reefs and cliffs limited possible landing sites to essentially two: the beaches around Hagushi on the island’s west coast and the Minatoga area on Okinawa’s southeastern end. Buckner decided to land his main force at Hagushi, while sending the 2d Marine Division would simulate a landing at Minatoga as a distraction. Once ashore, Tenth Army would secure Okinawa’s southern section before pushing into the northern end. A third phase would see the capture of some outlying islands. The campaign was expected to be finished by the end of May.

For his part, Ushijima realized that the overwhelming superiority of American firepower made holding the beaches impossible. Instead, he left small detachments in central and northern Okinawa, deploying the rest of his forces in the island’s southern section. His troops heavily fortified the area around Naha and Shuri, whose ancient castle capped a large series of ridges. Ushijima understood the importance of his mission. “Should we be unable to defend,” he told his troops, “the execution of the present war would be extremely difficult and would become a life-and-death problem for our nation.”

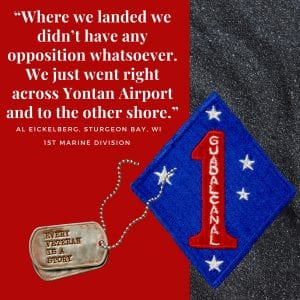

Nicknamed “the Old Breed,” the 1st Marine Division is the oldest active-duty division in the Marine Corps. Its members wear with pride the division patch which was designed by a Wisconsin veteran. Then-Lt. Col. Merrill B. Twining, from Monroe, designed the patch in 1942-43 after the Guadalcanal Campaign, while the division was in Australia. Both places are reflected in the patch’s design. V1994.17

Operation ICEBERG began with the 77th Infantry Division’s landing in the Kerama Islands on March 26th, 1945. Six days later, on April 1st, Tenth Army stormed ashore at Hagushi. Amazed American troops, expecting to meet heavy resistance, instead marched inland without seeing or hearing much of the enemy at all. Objectives like Yontan and Kadena Airfields fell in hours, rather than the expected days. In the 1st Marine Division, James Anderson, of Dallas, WI, remembered,

“The first day we fell into a long line of Marines, and we just marched right down the road, and there wasn’t any fighting at all.”

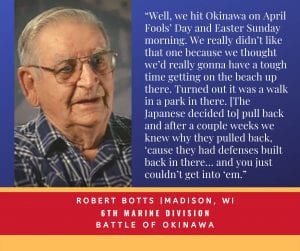

The Americans pushed forward, cutting the island in two on April 2nd. The next day Buckner unleashed the Marines into northern Okinawa ahead of schedule, while XXIV Corps turned southward. Within two days the 7th and 96th Infantry Divisions encountered strong Japanese fortifications, the first layer of defensive positions before Shuri. “Increasing resistance,” noted Buckner in his diary.

The quiet first days of the Okinawa invasion seemed surreal.

“The desperate and bloody resistance at the water-line that had marked every other invasion of the Pacific was entirely wanting,” recalled an officer in the 6th Marine Division. “Easter services could have been held in the open on a beach that had loomed in advance as one of the toughest of them all.”

But the lull was ending. In the Japanese Home Islands, 325 miles to the north, air and naval units prepared to enter the battle. On Okinawa the 32d Army steeled itself for the trials ahead. “Do your utmost,” Ushijima told his troops. “The victory of the century lies before us.”