By Russell Horton

Reference Archivist

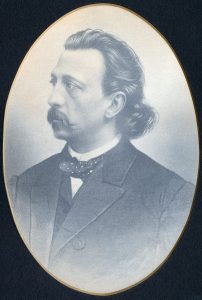

…justice seems to demand that they should be rewarded in a different manner for their patriotism than by a loss of the most important right of citizenship. – Governor Edward Salomon

Governor Edward Salomon

When the Civil War began in April 1861, many people thought it would be a short affair, probably over in a matter of months. But as time passed, it became apparent that the fighting would continue into 1862 and most likely much longer. As local and state officials began pondering the many ramifications of a long war, one of the issues that arose was voting.

With hundreds of thousands of Union soldiers serving far from their homes and their polling places, Northern states began wrestling with the issue of how, and if, they should be allowed to vote. State laws at the time required a voter to be physically present in order to cast a ballot but allowing soldiers to return home to vote was not feasible.

Wisconsin addressed this issue in a special session of the legislature in September 1862. Governor Edward Salomon passionately argued for allowing soldiers to vote in the field. After noting that Wisconsin would soon have as many as 40,000 eligible voters serving in the Union Army, he said, “The views of these brave and patriotic men should be heard through the ballot box and should have proper weight in shaping the destiny of our imperiled country.”

A little more than two weeks later, Wisconsin became the second state in the Union to pass legislation that allowed soldiers to vote while in the field. The law charged the three highest ranking officers in each company to act as election inspectors-ensuring the eligibility of voters, collecting and tallying their votes, and forwarding the results back to Wisconsin.

The law meant that soldiers’ voices were heard in the presidential election of 1864, a race that promised to decide the outcome of the Civil War. One candidate, incumbent Abraham Lincoln, vowed to continue the fight to restore the Union until it was won. His opponent, General George B. McClellan, ran on a platform of ending the war and seeking peace with the Confederate States of America.

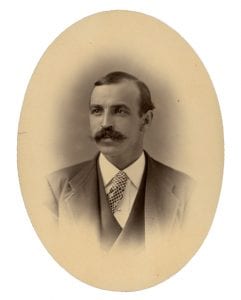

Asahel Gage of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry

The election weighed heavily on the minds of Wisconsin soldiers in the months and weeks leading up to it. In a letter home, Asahel Gage of the 2nd Wisconsin Infantry asked how the prospect of Lincoln being reelected looked in Wisconsin. He received a reply that “there is no doubt but Honest Old Abe will have to steer the ship another four years if God spares him.” Meanwhile Martin Ellison, a member of the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry, wrote in a letter to his family that, unlike many of his fellow soldiers, he planned to vote for McClellan. “I shall vote for the man I think best fitted to bring about an honorable peace…”

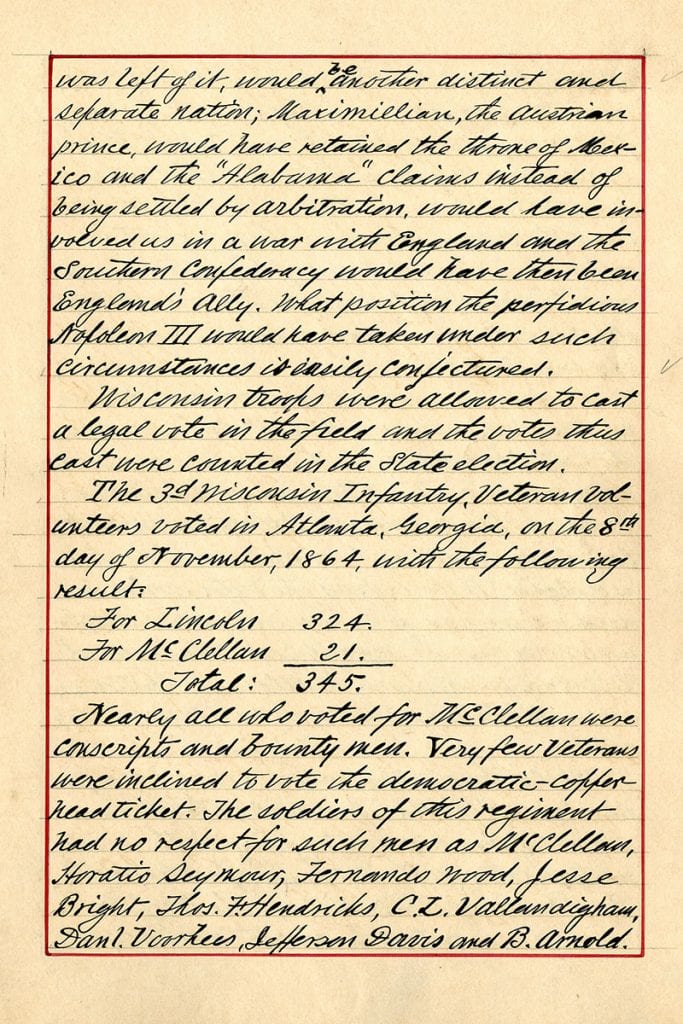

William Goodhue, of the 3rd Wisconsin Infantry

William Goodhue, a member of the 3rd Wisconsin Infantry from Brodhead, remembered the election in his memoirs. “Wisconsin troops were allowed to cast a legal vote in the field and the votes thus cast were counted in the State election. The 3rd Wisconsin Infantry Veteran Volunteers voted in Atlanta, Georgia, on the 8th day of November, 1864, with the following result: For Lincoln 324. For McClellan 21.” The final tally for all Wisconsin troops showed a similarly clear victory for Lincoln, who won 11,372 votes to McClellan’s 2,458.

The idea that American military personnel have a right to vote in elections, even when serving far from their homes, is an often-overlooked concept that first came out of the Civil War. As Governor Salomon argued in 1862, “…justice seems to demand that they should be rewarded in a different manner for their patriotism than by a loss of the most important right of citizenship.”

Excerpt from William Goodhue memoirs