Chester L. "Chet" Krause served with the 565th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion in World War II.

In honor of the 79th anniversary of the liberation of Buchenwald Concentration Camp during World War II, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum presents the story of veteran Chester L. “Chet” Krause, one of the first Americans to visit the camp.

On April 11, 1945, Buchenwald Concentration Camp, located near Weimar, Germany, was liberated by the United States military. Chester, an auto mechanic serving with the 565th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Automatic Weapons Battalion, was just a few miles away from the camp when he heard of its liberation.

A native of Helvetia, Waupaca County, Wisconsin, Chester was drafted into the United States Army in February 1943. He completed basic training at Camp Wallace, Texas. In the spring of 1943, the Army sent Krause to an anti-aircraft training camp in Camp Davis, North Carolina. He completed further auto mechanic training; he had previous experience living on a farm and maintaining tractors. Later, the Army sent Krause to Camp Stewart, Georgia, where he joined the 565th.

In the fall of 1944, the command sent Krause to England. Two months later, he crossed the English Channel and entered France on December 16, 1944, right as the Battle of the Bulge was beginning. Allied command sent his unit to Luxembourg City, assigned them to the Third Army, and tasked them with defending the Third Army Headquarters on the outskirts of the battle.

American troops began to move into Germany as the war continued, and Krause continued until he and his unit reached Weimar, Germany. As part of a battalion maintenance group, Krause was frequently on the move with nothing else to do except fix vehicles. While helping others alongside roadways, Krause learned of the liberation of Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Being only six or seven miles away from the camp, Krause and a group of men decided to go to Buchenwald that very day at around 5:00 pm. Krause notes that they were some of the first Americans to visit the camp as "tourists" and were there the day before General of the Army Eisenhower visited it.

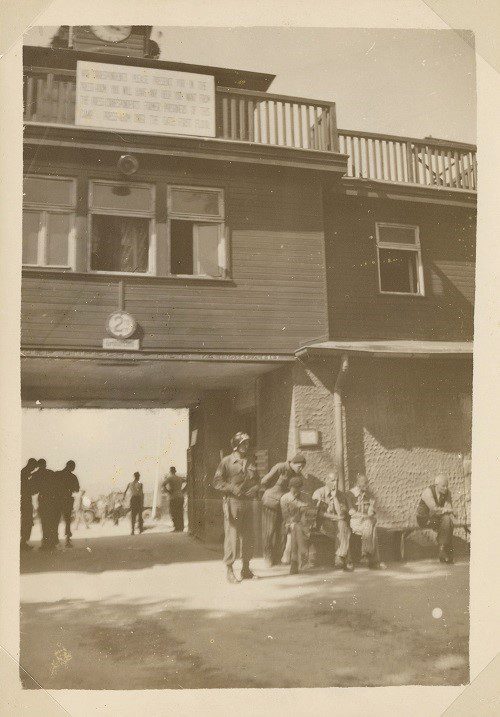

Entrance to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Photo by George L. Rambo, 892nd Air Engineering Squadron, United States Army Air Corps. WVM.Mss.2120, Box 3.

Upon entering Buchenwald, a teenage boy who spoke fluent English, greeted Krause. He took them to visit the hospital doctor, who asked the group for D-rations, which typically consisted of chocolate bars. The doctor gave tiny slivers of the chocolate to sick inmates who struggled to eat.

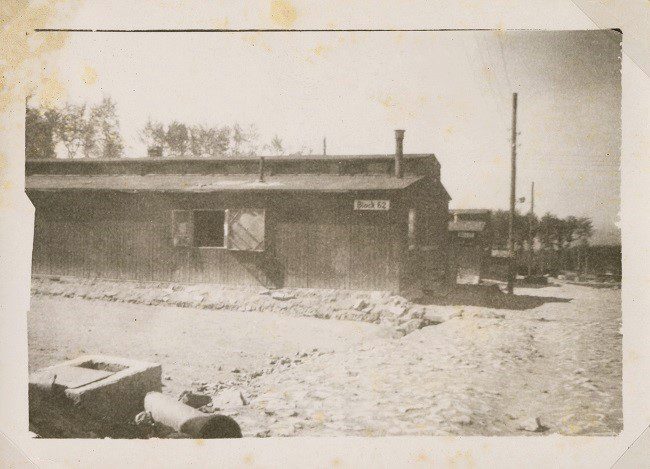

Exterior of Block 62 at Buchenwald. Photo by George L. Rambo, 892nd Air Engineering Squadron, United States Army Air Corps. WVM.Mss.2120, Box 3.

Krause visited the camp brothel before moving on to the upper camp. He describes visiting the upper camp, where most of the Buchenwald inmates slept. This area was organized into rows of barracks referred to as blocks. He noted these internees could speak some English, and when he visited them, they were boiling potatoes on a single stove in the middle of the barracks.

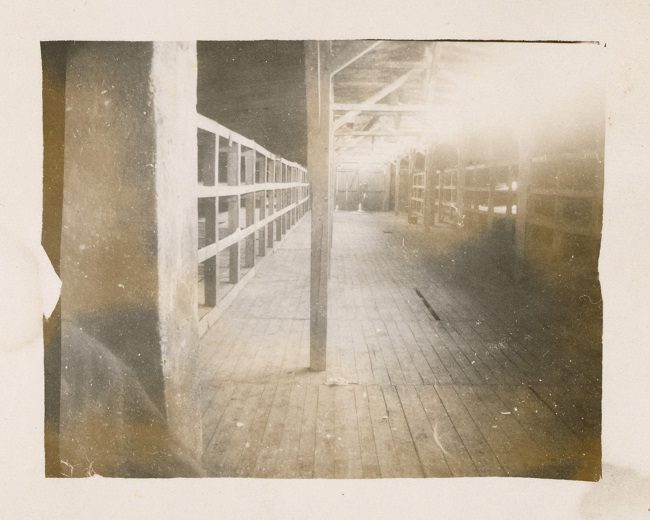

The interior of the barracks shows wooden bunks at Buchenwald. Photo by George L. Rambo, 892nd Air Engineering Squadron, United States Army Air Corps. WVM.Mss.2120, Box 3.

Next, Krause visited the lower camp, where German guards interned Jewish prisoners. Here, he talks about what he saw:

KRAUSE: But we left there and we went down to the lower camp, which was the Jewish camp, and that, I just, it's almost inconceivable that man can treat man that lowly, you know, that they-- their bunks were, I would say, oh, six feet wide, and that was enough for six people to sleep on, and they were, I would say eighteen inches tall and they were about six of them high, one, you know, on top of another. So, you know, it was six by six by, or six by seven or something like that, and there would have been thirty-six men sleeping in that, little cubby holes, you know, really something that was probably a foot wide and sixteen inches high. That is what that they had to sleep in, and sometimes they would sleep alternately feet and head and feet and head, but they never took a bath, and the stench in there was just ungodly.

Next, Krause describes what happened when people in the lower camp died:

KRAUSE: Anyway, when they would die at night, the next morning they would have to-- their own kind would take them out and down into that barracks, and they would put them in a little room, and then the next night they would come along with two-wheeled carts and pick them bodies up and take them up to the--

INTERVIEWER: Crematorium.

KRAUSE: Crematorium, yeah. So, and we did go to the crematory, but there were no bodies. There were bodies in carts ready to go to the crematory, but we didn't--actually, it wasn't operating when we were there, but there was piles of ashes out back that, you know, and I remember taking a series of pictures of all that crazy stuff, but I was awful careful who I gave them to. I mean, when I came home, when I was over there everybody wanted to see 'em.

INTERVIEWER: Sure.

Krause noted that visiting the camp helped reveal “the realities of the war.”

The "Poles Salute Their Liberators" banner was seen at Buchenwald after liberation. Photo by John P. Maertz, 9th Bombardment Division, United States Army Air Corps. WVM.Mss.901, Box 3, Folder 13.

Later in life, Krause visited New York City, where many Jewish immigrants moved before and after World War II. He recalls telling the story of what he saw at the concentration camp and how people in New York reacted to his story:

KRAUSE: And you know, I've been in New York City where, you know, Brooklyn and New York have a lot of Jewish population, and I told this story much like I have to you, and God, the first thing you know, there would be four or five people around me, you know, and they said, "Would you come tell our group that?" and I said, "Well, I'm going back home," but they said, "Well, we've got people that don't believe that," you know, "they don't believe that there were concentration camps and that they were treated this way," you know, and they were really, really concerned, and they were, you know, they don't often find somebody that had been to a concentration camp that-- in first person that could reveal it to them, you know, and so they were great.

Krause’s full interview is available by clicking here or the image below: