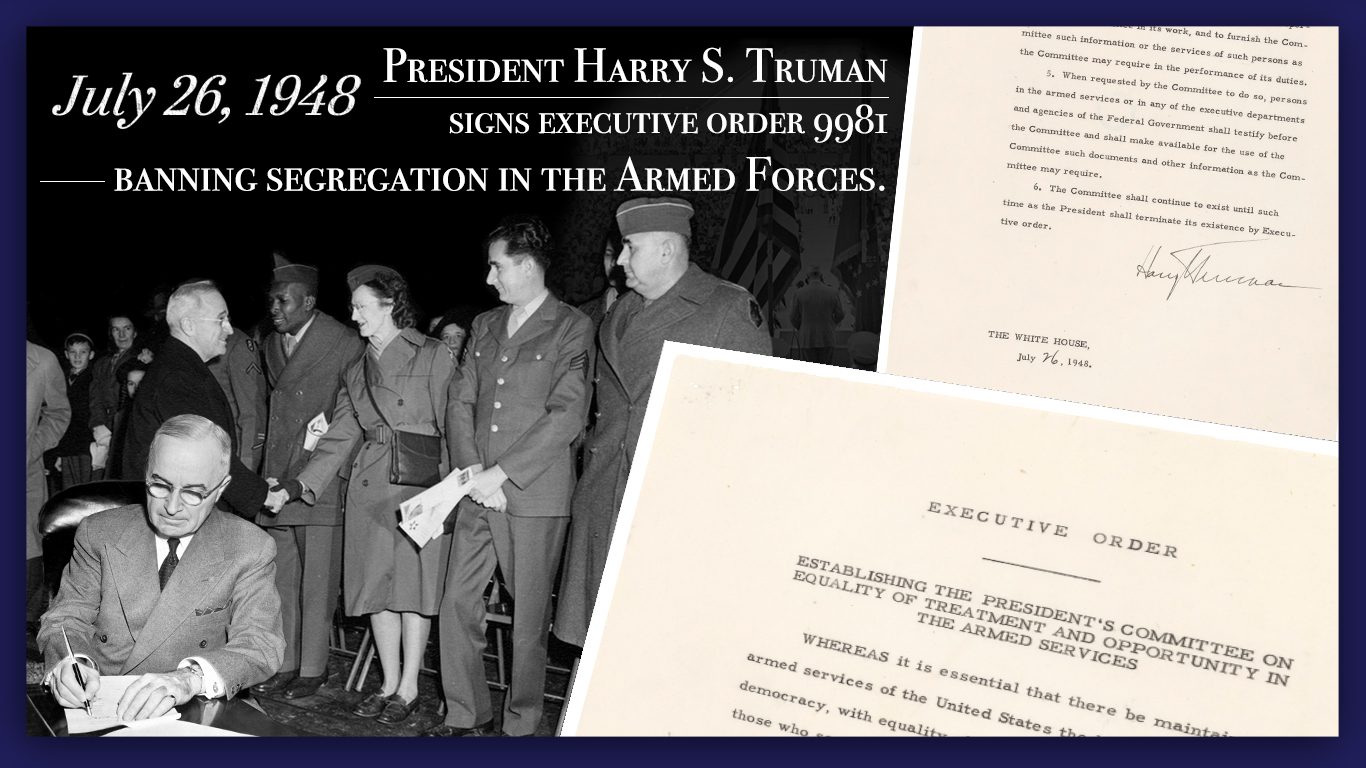

Truman desegregates armed forces. Image credit: PO1 Christopher Previc. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

What is the Executive Order 9981?

On July 26, 1948, President Harry S. Truman signed Executive Order 9981: The Desegregation of the Armed Forces. This order banned segregation in the armed forces and ordered the full integration of all branches of service. The order also mandated equality of treatment and opportunity to all person in the armed forces without discrimination because of race, color, religion, or national origin.

However, integration didn’t occur immediately after the order was signed. There was a slow progression between 1948-1954 before the military was fully integrated.

The Slow Process of Military Desegregation

Since the American Revolution, Black soldiers participated in United States' greatest wars including the Civil War, World War I, and World War II; however, despite their contribution they faced segregation and racial violence while serving. A. Philip Randolph, a black leader, spoke with President Truman and told him if he didn’t end segregation, African Americans would resist the draft. Knowing he would encounter resistance if he tried to get Congress to pass legislation, Truman signed Executive Order 9981 that allowed for the integration of the armed forces. Despite the implementation of Executive Order 9981 by President Truman, the desegregation process encountered resistance.

A Wisconsin Soldier’s Experiences During Military Desegregation

Major General Vance Coleman witnessed the process of desegregation during his 36-year career in the army. Eventually becoming the first African American major general from Wisconsin, he served in the U.S. Army with the 623rd Field Artillery, 1st Cavalry, and with the U. S. Army Reserve in the 84th Division (Training).

Service Photo taken of a shadowbox at the Celebration of Life ceremony for Maj. Gen. Vance Coleman June 17, 2022 in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Photo credit: U.S. Army Reserve photo by Sgt. Alyssa A. Blom. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Coleman was born in 1930 at Dermott, Arkansas. In 1942, his family moved to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He graduated from Boys Technical High School and enlisted as a volunteer in the army in December 1947. He served in Germany for two years, after which he left for Officer Candidate School (OCS). He was the first Black soldier to graduated from OCS. Commissioned as a second lieutenant in the artillery, Coleman was ordered to Korea.

He was assigned to the 623rd Field Artillery. He saw combat at Pork Chop Hill and his unit gave artillery support to the Marines at Inchon. He was under the Army National Guard artillery battalion comprised largely of National Guard members from Georgia, Kentucky, and Alabama. He was the first Black officer assigned to the racially integrated unit.

Coleman took shrapnel wounds in Korea and was evacuated to a general hospital in Japan. After leaving the hospital, he was stationed in the 1st Cavalry Division at Sapporo. He was honorably discharged in 1958.

Vance Coleman an Outstanding Soldier

Encouraged by a friend, Coleman joined the Army reserves in 1959. He was promoted to Captain in 1959. He was an officer in the 84th Division (Training). Coleman rose quickly in rank through schooling and command and staff assignments. In 1966 he was promoted to major, lieutenant colonel in 1974, full colonel in 1979, and major general in 1985. He commanded more than 3,000 Wisconsin reservists. Coleman was the first Black commanding general of the 84th Division (Training). He retired after 36 years of service.

During his military service Coleman received several commendations during his service. He was awarded the Purple Heart, Meritorious Service Medal OLC, Army Commendation Medal, Good Conduct Medal, and National Defense Service Medal among others. He passed on September 1, 2021.

Oral History Interview

In the following video clip, Coleman remembers his first assignment after finishing Officer Candidate School. Because he was Black, he was reassigned to a transportation company.

INTERVIEWER: They -- Ok you got that bar on your shoulder -- got a job for you, where to?

COLEMAN: First assignment was with the 31st Infantry Division, Dixie Division, out of Alabama. They call it National Guard units for Korea. And I reported -- I forget -- I reported in the afternoon to headquarters, and there was stunned silence.

INTERVIEWER: Why?

COLEMAN: Didn't know what to do with me. [Laugh] So I was told to go back to quarters to they call me. I hadn't gotten any quarters yet. I went to -- DOQ was across street from the officer's club. So I went to the DOQ there. I went to the wrong one. Your DOQ was down there somewhere.

INTERVIEWER: Oh, Lord.

COLEMAN: So I said, Okay. I was a little hungry, so I went across to the pub and got a bite to eat. Can't go there either. Anyway --

INTERVIEWER: You know looking back, it's hard to believe, you know, I have lived through all that. It's another story.

COLEMAN: So I ended up getting reassigned to a transportation company. And I couldn't believe -- I can't believe -- Just changing orders from combat unit to a transportation company. I served there about a year and a half. In the process I got married. Oh, no, before that, I volunteered for Korea. And I got thanks you are not needed at this time. I got married, and a month after I got married, I got orders for Korea. Got assigned to -- there again, I got assigned to a National Guard unit. The 623rd Field Artillery Battalion out of Kentucky, Georgia, and Alabama. But well received, of the battalion commander and [inaudible] military members from Kentucky. And the senior officer told me he was from Alabama. No, Patrick was from Alabama, and Tony was from Georgia, Georgia Tech matter of fact. All the NCOs were from those three states, but they were good, but there was a top gun was O'Mere first sergeant. O'Mere didn't care who you were, you were soldiers. [Inaudible]. But the chief firing brand of field artillery was the Senior NCO of guns. Black was from Kentucky who picked up where I left off at OCS and taught me the real Field Artillery.

COLEMAN: That was a good assignment.

INTERVIEWER: You were there how long?

COLEMAN: Ten months.

INTERVIEWER: Ten months.

COLEMAN: I was there ten months. I think a couple months before I was supposed to rotate on the rotation system I was ended by Field Artillery. We had that.

To learn more about Vance Coleman the full interview is here.

To explore more Wisconsin veterans' stories click here.

Desegregation in the Military was written by Tanairi Diaz-Lopez, Summer 2023 Intern at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum.