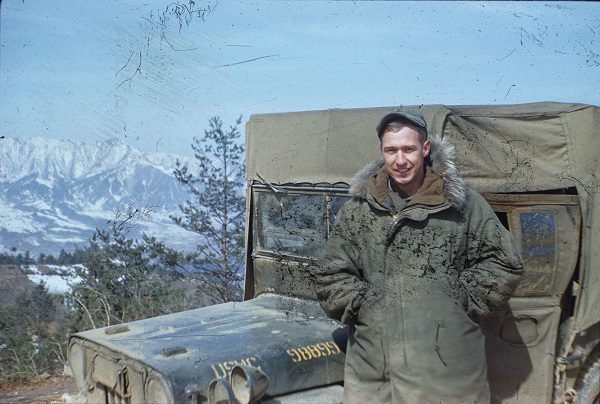

J. Birney Dibble in Korea. WVM.1323.I072.

During the Korean War, J. Birney Dibble, an Eau Claire, Wisconsin resident, served as a naval surgeon on active duty in the United States Naval Reserve. Though administratively assigned to E Company, 1st Medical Battalion, 1st Marine Division, Dibble spent much of his time at the forward aid station attached to 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division during the Korean War.

In the middle of World War II, Dibble, at seventeen, voluntarily enlisted in the Navy V-12 officer training program in 1943 and attended Duke University as a pre-med student before going to Camp Lejeune as a corpsman. There Dibble worked in an orthopedic ward at Camp Lejeune, treating Marines injured in campaigns at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Following World War II, Dibble stayed on active reserve status in the Navy while completing medical school at the University of Illinois in Chicago.

He was completing a two-year internship when the Korean War broke out and knew he would be “doctor drafted.” So, Dibble asked the Secretary of the Navy permission to complete his medical internship before deploying to Korea. The secretary granted this request. He later volunteered to serve with the Fleet Marine Force (FMF).

Dibble has an extensive collection with the Wisconsin Veterans Museum (WVM). His collection includes slides, video recordings, papers, and photographs that can be found in the WVM Archival Collection at: https://wisvetsmuseum.catalogaccess.com/archives/50039. Additionally, Dibble wrote Taking of Hill 1052, a fictionalized account of his experiences in Korea that can be found at libraries throughout Wisconsin see: https://wisvetsmuseum.worldcat.org/oclc/33188609. Lastly, his complete interview may be found in our oral history collection at: https://wisvetsmuseum.com/ohms-viewer/render.php?cachefile=OH_01246.xml. During his interview, he provides commentary on his book.

Below are some audio extracts from his oral history interview and photographs from his collection.

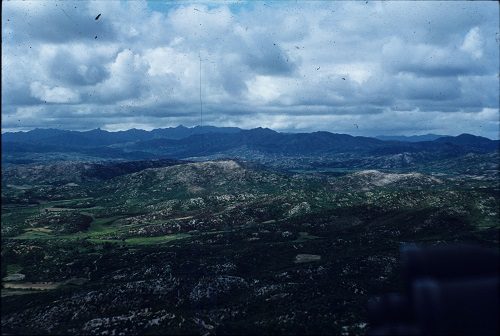

Naval surgeons training for combat at Camp Pendleton, California. WVM.1323.I075.

DIBBLE: and then I went to Cook County Hospital for a two-year rotating internship, male surgery, female surgery, male medicine, female medicine, obstetrics, the whole range of subjects. I spent two years rotating there. Meanwhile, the Korean War had broken out, so I knew I’d be going back in. The doctor draft had started and there was a ruling that affected a lot of doctors, that if they’d been in seventeen months or more in the Second World War as a doctor, they were ineligible for recall or drafting. And I knew one doctor who’d been in sixteen and a half months as a doctor, but didn’t have that extra two weeks and they got him. I also knew a doctor who’d been enlisted during the Second World War, actually had been wounded in the European theater, and he was called up because he was now a doctor.

J. Dibble Birney and Edna Baird. J. WVM.1323.I172.0.

DIBBLE: And I soon had a pipeline going from my home in Illinois, my wife’s home actually in Springfield, and she started sending me popcorn and brownies and things like that, and most of that stuff actually came through.

HEALEY: How long did it take for mail to reach Korea?

DIBBLE: It was a month of– two weeks each way.

HEALEY: Okay.

DIBBLE: You’d write the letter. It would go out- if we weren’t in actual combat or on the move- it would go out the next day, go back to regiment, from there to 1st Marine division headquarters, from there on the east coast it would go to Hum-nung [sp??] and then by boat home. There was almost no air mail at that time. It began while I was there. We got these little “V for victory” air mail things, then of course it was almost two weeks by boat and then to Springfield, so it was a good two weeks. The packages took longer. They took up to a month. Yeah, they were pretty popular, and you know, one thing that we didn’t have? We didn’t have enough of the little mantels for our kerosene lanterns. We would run out. So I wrote home and had my wife, Edna, send me a big box and when it came, I just distributed two or three to everybody in the battalion headquarters, and they were really appreciative because they, I mean, they break so easy you know, once there, if you’ve ever used one. It’s a little bag to begin with, but when you touch a match to it, it flames up and it just becomes a–very, very fragile. So if you’re on the move, every mantel on every trip that we took would break and you’d have to put a new one in it. Anyhow, just a little sideline as to what was important and what wasn’t [laughs].

Forward bunker on line of 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, 1st Marine Division. WVM.1323.I090.

DIBBLE: Bob Kimball and I alternated. We had a front line right in the main trench line, a forward aid station that was in a big bunker, big compared to the others. I would guess it was probably, oh eight or ten feet deep and five or six feet wide. No, more than that, probably eight or ten feet wide too, and about four feet high, so you’re always crawling around. We would go up there. We always had two corpsmen in that bunker and with a doctor there was plenty of room to sleep so that we would be there and that was in George Company. We had three companies in 3-5. We called ’em George, Howe, and Ivan. Those have changed, I understand, quite a bit. It was Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog, Easy, Fox, George, Howe, Ivan. Those were the battalions in the 5th Marines and in the 1st Marines and in the 7th Marines also. We had–in George Company, it was almost always in the center between Howe, and Ivan. So, where we could, we had our first aid station in the center in George Company.

Commemorative emblem, United Nations Command. V2021.059.9.

DIBBLE: We had the Marines, Korean Marines on our left flank. They were on Kimpo peninsula. We had the Commonwealth Division on our right flank. That was the Brits and the Aussies and the Canadians and New Zealanders, the Danish and Swedish troops -not very many – Indian ambulance teams, a Turkish brigade, I don’t know how many they had, about two or three hundred, and then there was the ROK, the Republic of Korea, we called them the “ROKS” and two divisions on the other side of the Commonwealth Division.

HEALEY: How much contact did you have with those other country service members?

DIBBLE: Practically none. The one contact–one contact we did have periodically, the Turks were night fighters. They were used primarily, well they blocked one segment of line, but their primary purpose was to infiltrate at night the enemy lines and take prisoners for interrogation, and they would usually go out from their lines and come back through their lines, but every once in a while, they’d come back through our lines, and boy they were tough guys. They didn’t carry any weapons, except a knife because they, if they had them, they might be tempted to use them, and if their discipline wasn’t one hundred percent–so their officers didn’t allow them to carry any, they carried a knife, and they would just literally hold it against the prisoners. They would sneak up on peripheral guards and take them by the–from behind, and if they struggled too much, why they would just slit their throats. But if they went quietly, they’d bring them back. So, we would see every once in a while, like not all that often, every couple three weeks, a Turk coming back or two Turks often with a prisoner for interrogation.

Bunker Hill in Korea. WVM.1323.I124.

DIBBLE: After the Battle of Bunker Hill, which went from Friday night, all day Saturday, all day Sunday, Sunday night until Monday morning, all the 7th Marines, most of the 3rd Battalion. We triaged one thousand-four Marines, WIAs in that three-day period. I know that because George Dupro, my senior warrant officer and I sat down and counted the EMTs, the emergency medical tags and there were one thousand-four. We didn’t operate on all those, there’s no way that we could have on that. So, we just had a steady progression of patients into the operating tent, into the minor operating tent, into ward four, where those that were hopelessly wounded and we couldn’t take the time or the personnel to, we just let them go, one of the toughest decisions, and the decision that I had to make as a commanding officer, whether to try to save life from that, I’ll never forget some of them. And there was a steady progression, procession of Sikorskys helicopters who’d come in and take six off to the Constellation, six off to Hope, six to another medical company.

(L to R) Fr. Barlik, Col. Nan, Dr. Lee, and unidentified ROK officers. WVM.1323.I114.

DIBBLE: I could tell you about Dr. Lee.

HEALEY: Okay.

DIBBLE: We did have one doctor, Korean doctor. He’d been with the Army’s Hourglass Division, right at the beginning of the war. So, he was trapped up in the Chosin Reservoir area. You’ve heard of that?

HEALEY: What’s the Hourglass? You said that the Hourglass Division?

DIBBLE: Hourglass Division, I think it was the 7th Cavalry.

HEALEY: Okay.

DIBBLE: I’m not sure about that. He called it the Hourglass all the time.

HEALEY: Alright.

DIBBLE: And uh, literally fought his way out with the Army that he was attached to, but it was the Marines at Hungnam-ni that rescued him, and he decided to stay with the Marines, and so he stayed with that Marine group till they were evacuated, and then they recognized that he had some surgical talent and sent him up to Easy Med before I met him. Lee Yong Kuk [sp??]. His father had been killed by North Koreans on the steps of the Presbyterian Church. They were Christians in Seoul, and I visited him and his mother and his wife a couple times while I was at Easy. Being the commanding officer, I could take off for a little while once in a while.

HEALEY: Was his father killed in the 1950s?

DIBBLE: In the fifties, when the North Koreans–first time they came through Seoul and drove the entire Army down to the Pusan perimeter. Yeah, and he was good at what he did, and we became very close friends, spent more time probably with him than with any of the others. You know how you do that sometimes with other people. It just seemed to click.

HEALEY: English speaking?

DIBBLE: Oh yeah. He spoke English almost perfectly, except for when he was telling me about the time the father was killed, then he broke down. We were in Seoul and just visited the Presbyterian Church. Big imposing church, on that tape you may remember seeing it. And we kept in contact, and I’d been home in my surgical residency at Cook County Hospital when he wrote and said that he would like to have a surgical residency somewhere in the states, could I help him? Well, I did have some contacts and one of them was at Colorado, University of Colorado, and so he came over here and got a full four years of surgery training, residency. He went back to Korea, got on the staff of one of the major hospitals, and the last– in nineteen-eighty or eighty-one, when I visited him there, he was chief of surgery at this hospital with about seventy or eighty surgeons.

HEALEY: And where’s that hospital located?

DIBBLE: In Seoul.

HEALEY: Okay.

DIBBLE: And I was on Guam, living there, and I got a letter from him. We corresponded periodically. Said, “Did you know that there’s a Korea re-visit program? Whereas if you get to Korea, the government will put you up in a hotel and furnish transportation for you to go back to the places where you were when you were in combat here.” So we went, and spent a week with him and his wife. It was Edna then. I lost her a few years ago after fifty-two years of marriage. Any rate, he showed us around and by then he had been doing transplant surgery. He was the first surgeon in Korea to do a kidney transplant and then he started doing other transplants. And I went back again eight years ago and just visited him for one day. He was in rather failing health, but that’s the contact I had with him over the years.

Helicopter evacuation from 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines. WVM.1323.I102.

DIBBLE: I was–just sort of as an aside, people would ask me, “Do you watch MASH? Do you like it?” And for a year or so, I just couldn’t watch it. It was so unrealistic. I could appreciate the humor, Alan Alda and the, what’s his name, the cross dresser, and the Colonel, but it was so unrealistic that I’d have to keep saying to Edna, “That’s not the way it was. They couldn’t possibly do that. No.” And she said one day, “Maybe you just shouldn’t watch.” Well, I went to a meeting, Massachusetts General. I was talking to a guy and found out that he’d been in Korea, and that I had been. He said, “Oh, I bet you enjoy watching MASH.” I said, “I just can’t watch it,” then went through the same stuff, and he stopped me, said, “Do you watch Hogan’s Heroes?” And I said, “Oh yeah, I love it. That is really funny.” He said, “Do you suppose that’s the way it really was in a German prisoner of war camp?” “Okay, I get your point.” And from then on I could watch it, realizing that it was satire, it wasn’t supposed to be realistic, and they did have a few programs once in a while that’d be very poignant and would remind me of the way things really were, but distilling you know martinis with that– oh it was–and course, Alda, Alan Alda is funny.

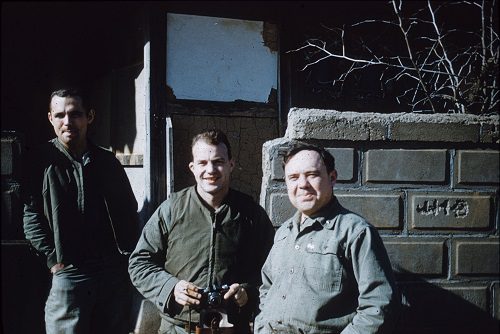

(L to R) 2/53 Spencer, Frank Roach, and Cdr. Ayers, 3/5 Marines. WVM.1323.I135.

HEALEY: Something you wrote a little bit about was those, and you mentioned them under different titles or name during each war or conflict but the shell shock–

DIBBLE: Yeah, it was called shell shock in the First World War. We called it combat fatigue in the Second World War, and we called it a neuropsychiatric evacuation in the Korean War, just a change of terms for the same situation where a man has just reached his tolerance under fire.

HEALEY: How were those people assessed?

DIBBLE: Frank Roach, Dr. Roach, was our division psychiatrist, and he was back in division and saw cases back there until I came back to Easy. He’s a good friend of mine from Cook County, and so he asked Commander Ayers permission if he could just go to Easy. So he came up and was with us, and I have pictures of him.

HEALEY: Oh, he was assigned full time?

DIBBLE: Yes. Oh yeah, and that’s all he did. He took his job seriously. The evacuation rate, if you take a hundred casualties evacuated, two of them would be neuropsychiatric in the Marine Division. The other ninety-eight would be war wounds. ‘Course this was a wound too I guess you might say, and he would be asked to evaluate the patient, you might call, the Marine, the evacuee, and determine, “Did this man know right from wrong?” And if he did, was he able to adhere to the right or was he unable to adhere to the right? He’s ordered into combat, make a patrol, he cowers in the back of his bunker and won’t move. Is he a neuropsychiatric, or should he be discharged, or should he be treated, or should he be treated at home in the states, or treated in battalion, or back at the medical company? He had all these decisions to make. “Perhaps, we can get him to the point where he can actually go back into combat?”

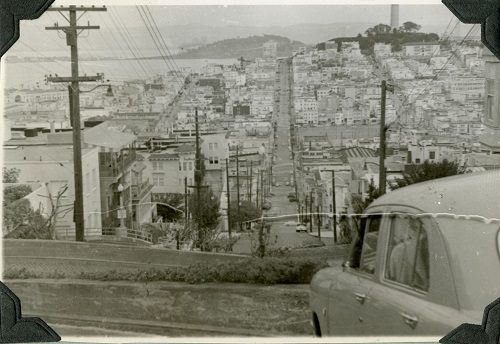

Dibble's photo of San Francisco. WVM.1323.I233.03.

DIBBLE: and eventually I did get orders to this ship, and they were gonna land in San Francisco. Meanwhile, my mother had gone home, which I thought was–I didn’t think anything of it at the time, well yes that’s proper, but I thought since, that must have been a difficult thing for her to do, rather than to wait for me. Knowing that I would be with my wife–would want to be with my wife for the first few days and weeks at least. Wally Indeck, I haven’t thought of his name for years, was the Army officer I played bridge with. He–his wife was waiting for him too, and I can remember standing on the ship and looking down and they actually had a band down there, an Army band walking as they played the whole time we were off loading, and Wally and I decided that we would go to the Top of the Mark. Did you ever hear of that?

HEALEY: No.

DIBBLE: It’s a real expensive restaurant at the top of the biggest hotel in San Francisco, and it was up on a hill. We had a big dinner and were walking down to where we parked our–Edna had driven our car out. Wally’s wife had a car too, but we were in our car that night. Any rate, I remember going by a soda fountain, we called it then, and there was a great big banana split in the window [laughs]. I said, “I gotta have one of those.”

HEALEY: You hadn’t seen one of those for–[laughs]

DIBBLE: –hadn’t seen one of those for, well a year and a half, well more actually, ’cause almost two years by then. So, we went in, and I got a banana split. Funny how you remember a thing, and Wally laughed about that so hard.

HEALEY: So how long did you stay in San Francisco?

DIBBLE: Just three days.

Taps at memorial service, Camp Tripoli, Korea. WVM.1323.I107.

DIBBLE: Yeah, for some years now, I’ve been going to the American History classes at the local high school, which has about–well there are five classes with about twenty in each.

HEALEY: And that you said is Memorial High School?

DIBBLE: Yes.

HEALEY: Here in Eau Claire?

DIBBLE: Eau Claire. They, the teachers, there’re two of them – one has three classes, one has two – that show my video, now it’s in DVD of course, to the class the day before I come. So the entire fifty minutes is questions, and they, soon as I come in and I’m introduced, the hands just start going up, and they go up for an hour, almost an hour, and they’re still some hands in the air when the bell rings. They’re just so exciting for me. It’s tiring too, to stand on my feet from 8:30 in the morning until 3:30 in the afternoon with a half an hour break, forty minute break for, but the enthusiasm of these kids about the Korean War is really astounding to me ’cause they’re getting a background in the Korean War that ninety percent or ninety percent of the American public have no idea about. It’s called the Forgotten War, but I disagree. It’s not forgotten. It was never known, and you can’t forget somethin’ that you never knew. I came back to Cook County and nobody, almost nobody, knew about the war, only those that, particularly the patients. I asked twenty-five young girls on the OB ward once if they had heard of Korea, this was almost three years after it started, one of them had heard of Korea and that was ’cause her brother had been there.

HEALEY: That’s amazing.

DIBBLE: It is.

HEALEY: I, I didn’t realize that, that it had so little visibility in the fifties.

DIBBLE: And yet we had a dedication, I think that was that same year, maybe that also stimulated my writing, of the Korean War Veteran Monument in Washington, D.C.

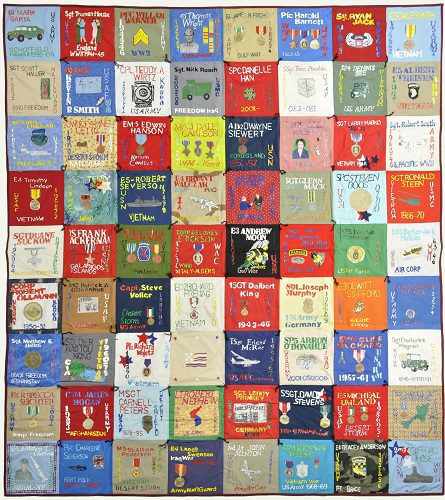

Veterans quilt made by social studies students at DeLong Middle School in Eau Claire, Wisconsin. Presented to Wisconsin state senator Kathleen Vinehout in commemoration of Wisconsin veterans. V2018.069.1.

HEALEY: And how did you get to Eau Claire, Wisconsin?

DIBBLE: I had met a young man, Ralph Hudson, from Mt. Morris, Illinois on a train going to my first duty station way back in 1943. He was at one end of the car and I was at another, and we kept looking at each other. I thought I recognized him. Well, we got together at Lynchburg, Virginia and found out that he was, lived in Mt. Morris and I lived in Rochelle, and we played each other for several years on the basketball forward in the same conference. So naturally we looked familiar but didn’t really know each other. Oh he and I stayed friends, medical school, internship, residency, and decided to go into practice together, and we wanted to go into Minnesota or Wisconsin, and so we literally just sat down with an atlas or a map and picked out ten places in northern Wisconsin, ten places in northern Minnesota and investigated all of them using Chamber of Commerce, and we knew an amazing number of doctors practicing in these towns, and we get information about the town, the living, and just–and then we narrowed the field down to about five in each one, and then we just took two weeks off with our wives and drove up here, and we went to–we eliminated Milwaukee, Madison, Duluth, Superior, Minneapolis as being too big. So, we went to Rhinelander, we went to Eau Claire, we went to Stevens Point and Ely, St. Cloud and some southern Minnesota, well near it, eventually just narrowed it down to St. Cloud and Eau Claire and then decided that Eau Claire had two surgeons who were board surgeons, American Board of Surgery. St. Cloud had seven, so we figured we’re gonna get a better start ’cause we’re just gonna hang up our shingle, you know? “Ralph Hudson and Birney Dibble, world’s great surgeons” and wait for the people to come in, and they did, slowly.