![Juneteenth [Converted] Juneteenth Flag](https://wisvetsmuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Juneteenth-Converted-150x150.png)

Juneteenth: A New National Holiday with Origins in 1865

Even though President Joe Biden signed legislation making Juneteenth a national holiday on June 17, 2021, as is the case with the Wisconsin Veterans Museum, the origin of Juneteenth lies in the U.S. Civil War, which was fought from April 12, 1861- May 26, 1865.

![Juneteenth [Converted] Juneteenth Flag](https://wisvetsmuseum.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Juneteenth-Converted-150x150.png)

The Emancipation Proclamation: What Did It Do?

On January 1, 2023, we recognized the 160th anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation taking effect. Originally announced the previous September after the Battle of Antietam in 1862, the Proclamation didn’t go into effect, however, until the start of the new year in 1863. The Proclamation was without a doubt a major turning point in the war. No longer could it be said that the war was just for the preservation of the Union and to stop states from seceding. Now it truly and officially was a war to end slavery.

However, the proclamation was limited in its ability to end slavery and was conditional as to location and application. For instance, it technically only applied to those held in enslavement in the states that had joined the Confederacy and were currently unoccupied by Union troops. This was a political move to keep the loyalty of the states that had permitted slavery before the war that then were along the border between the Union and Confederacy but hadn’t officially seceded from the Union. It was a limited but strategic move that was at least a step in the right direction at a time when there was still some uncertainty as to what the Union was fighting for.

The 13th Amendment and General Order No. 3

Not until the proposal of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution in 1864 and its passage through the Congress in January 1865, was slavery proposed to be illegal in all states and territory of the United States. And though it passed in Congress in January of 1865, the 13th Amendment still required ratification by the states before it would become enforceable law. By the 19th of June 1865, only 22 states had ratified the amendment of the requisite 27.

Therefore, when the first Union soldiers arrived on June 19th on Galveston Island and began reinstating Federal authority over the former Confederate state, the Emancipation Proclamation was still the standing executive order to be enforced by the U.S. Army even two years after it was issued. Though we think of the Emancipation Proclamation in terms of “ending slavery” in 1863, that’s not entirely true. It certainly wasn’t universally known or abided by across the country, thus the reason and significance to the deliberate choice to include it in General Order No. 3 as soon as Union troops arrived.

The Emancipation Proclamation's Military Component

We often think of events in history as inevitable. However, when the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, the war had only been going on for a year and a half and Union military victory was far from a guarantee. Up to that point the Confederates had won five of the seven decisive battles around Washington DC and in Virginia. Things were faring better out west under commanders such as Grant and Sherman, but there was still no guarantee of Washington DC’s safety, much less a victory that would end the war in favor for the Union. Battles that are common terms in history textbooks today such as Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Sherman’s March to the Sea hadn’t occurred yet and no one knew how exactly the Confederacy would meet its end. But Lincoln’s executive order of the Emancipation Proclamation did also provide a military component that would lend itself to bringing about that ultimate victory.

Lincoln said with the Proclamation that “I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable conditions, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.” Thus, introducing the option for formerly enslaved individuals to volunteer to serve in the U.S. military and play a role in spreading the Emancipation Proclamation to all those still enslaved in the Confederacy at that time.

General Order No. 3 and the Coincidence of Assignment

On June 19, 1865, nearly two and a half years after the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect, Union General Gordon Granger issued General Order No. 3 in Galveston, Texas, which informed all present of the Presidential order known as the Emancipation Proclamation. For many it was the first time that they had heard officially that enslaved African Americans were now free and that the Civil War had ended.

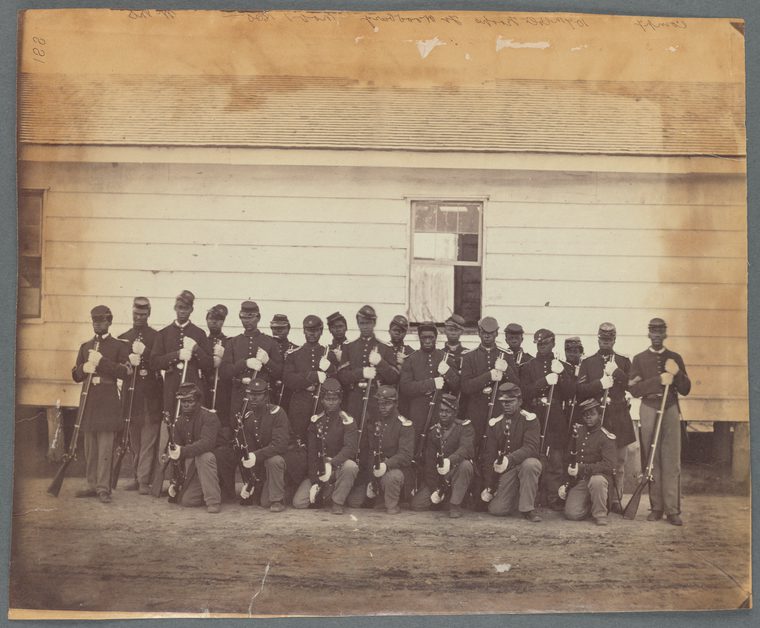

A coincidence less well known that involved with General Order No. 3 was that the United States Colored Troops (USCT), composed of free and recently liberated enslaved African Americans, were in Galveston from June 18-20, 1865. The XXV Corps, made entirely of African American units, was ordered to Brownsville, Texas located along gulf coast at the border with Mexico. Storms and other issues forced the convoy of troop ships to stop at Galveston to replenish supplies from June 18-20th before continuing to Brownsville. Those who disembarked on shore included soldiers from the 28th, 29th, and the combined 26th and 31st Regiments of the USCT.

Though that historical fact is documented in the official unit histories and reports, such a factual report could never adequately convey the true emotional impact of the scene in Galveston of the Union troop landing, which included the USCT regiments, and the circulation of the order that “all slaves are free.” Consider, for those newly freed people in the city of Galveston, not only hearing the news but then seeing men like them wearing the blue wool uniform of the United States Army and bringing an end to the Confederacy and slavery as they knew it. It’s a powerful image to say the least. Not only were those there now formerly enslaved, but it was already people that were formerly enslaved themselves that had volunteered to fight in the war, that were now bringing that news and enforcing it with full military authority of the U.S. Army.

"Company of colored troops" The New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1865.

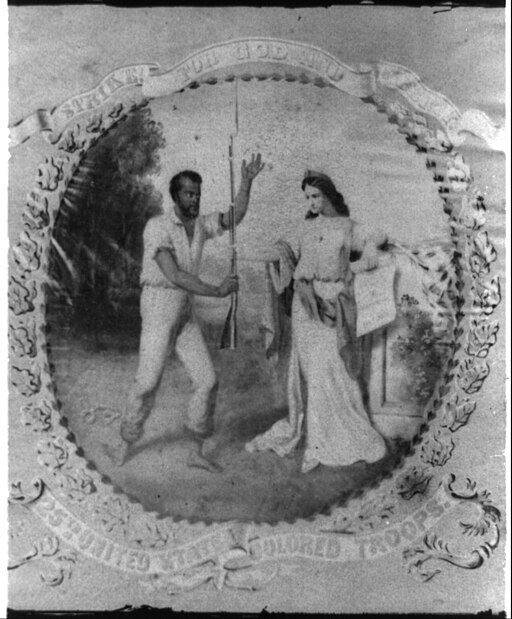

25th U.S. Colored Troops regimental flag depicting African American soldier standing next to Columbia. Library of Congress

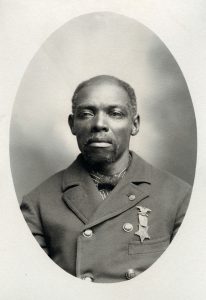

Horace Artis served in Co. F of the 31st Reg USCT. He later settled in Appleton. WVM.1044.I006

Two Wisconsin Men Who Served in the USCT

Though the rosters of the units don’t indicate the exact names of those elements of the USCT regiments that went ashore versus those that remained on the transport ships, we do know that at least two future Wisconsinites were members of those units at that time. Future Madison resident, Howard Brooks, who served in Co. H, 29th Regiment USCT, and future Appleton resident, Horace Artis, who served in Co. F, 31st Regiment USCT may well have been among those on shore when the order was issued on June 19th.

Howard Brooks was born enslaved in Virginia, gained his freedom during the war, and joined Company H, 29th USCT. Horace Artis was also an enslaved person born in Virginia near Norfolk. During the war, after the Emancipation Proclamation was issued, he sought his own freedom within the Union army lines and joined the 31st USCT in Washington DC.

Both of Brooks and Artis’ regiments participated in the siege operations outside Petersburg and the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia – including many battles that led to the eventual capture of the capital and completely collapse of the Confederate government. Their units then participated in the pursuit of the fleeing rebel army under Robert E. Lee and witnessed their surrender at Appomattox. Though that surrender didn’t cleanly or completely end the Civil War, it certainly was a significant event in the final chapter of the national narrative of the conflict. But for those of the 29th and 31st USCI, such as Brooks and Artis, that were born into enslavement in that same state that for four years was the political center for the Confederacy that fought to keep them enslaved, one can only imagine the profound impact it had to witness those final events of the war.

After the surrender of the Confederate army in Virginia, both of Brooks and Artis’ regiments were transferred to guard the US Border along the Rio Grande to protect against Napoleon III’s troops that were fighting in Mexico. They boarded troop ships and sailed for Texas. As we’ve recounted, the ships had to divert to Galveston for supplies before their destination. And it just so happened, then, that they were there to support the landing at Galveston on that historic day.

After his service, Howard Brooks took up residence in Madison, Wisconsin and eventually became one of the first African Americans to receive his pension for his Civil War service. Horace Artis settled in Appleton, Wisconsin and was a proud member of Appleton’s Grand Army of the Republic veterans’ post – the Civil War equivalent of today’s American Legion and VFW.

The Work "to create a more perfect union" Continues

As people gather to celebrate Juneteenth and what it means for our communities, we also reflect on the historic celebrations among the African Americans who had gained their freedom in Galveston in 1865, which continued the nineteenth of June in future years. Celebrations spread to other parts of the country after World War II and today Juneteenth is now a federal holiday to commemorate the freedom of enslaved African Americans. It is important to remember that this is not just a holiday for segments of our communities today. It is truly and rightly a national celebration - to elevate and acknowledge an evolutionary step of our nation with the end of slavery. Our Declaration of Independence, written in 1776 declared “all men are created equal.” It took two years for the news of the Emancipation Proclamation to reach Galveston, Texas on June 19, 1865 – roughly 90 years after those famous words were written.

This holiday is an important celebration of freedoms finally gained, and an equally important reminder that the work “to create a more perfect union” as mentioned in the Constitution is never truly done. It takes deliberate work to continue to improve our country and society. And truly, as we reflect on what that means through these patriotic holidays from Memorial Day, to Juneteenth, and July 4th, isn’t that what the sacrifice of all those that have gone before us was all about? To make tomorrow a better world than what came before?

Juneteenth: How Wisconsin Was There at the Beginning was written by Kevin Hampton, Curator of History at the Wisconsin Veterans Museum.