By Andrea Hoffman, Collections Manager

Certain pivotal events in our nation’s history have remained “where were you when” moments for all who lived through them, with one of the most prominent being the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor 77 years ago this December. While most of our World War II veterans’ stories began after the call to “Remember Pearl Harbor,” these are a few of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum collections of those already serving their county in Hawaii on that fateful day, witness to the infamy firsthand.

Arthur G. Rortvedt, Mss2003.003

Arthur G. “Art” Rortvedt of DeForest, Wisconsin registered for the draft in March on 1940, but preferring not to go into the Army, enlisted in the Army Air Corps instead. He completed his basic training at Wheeler Army Airfield, and was assigned to the 58th Bomb Squadron at Hickam Field one month before the attack. Rortvedt later credited his survival that morning to choosing not to eat breakfast in the mess hall, the location of many of Wheeler’s casualties. During a WVM oral history interview done in 1999, Rortvedt stated,

We heard the explosions and thought it was our Navy training, then we saw the Japanese aircraft…We got organized and I was on a .50 caliber machine gun and I was firing at the aircraft in the second wave. There was confusion; we could see the third wave that was bombing at a higher altitude. Some of our aircraft took off, but they did not find the Japanese ships.

Rortvedt spent the remainder of the war on Kanton Island and Makin Island working as an aircraft mechanic. He later re-enlisted and served in the Air Force until 1950.

Harold Schleusner, Combat Air Crew badge, V2009.21.3

Harold “Chief” Schleusner of Bruce enlisted in the United States Navy in 1939 at the age of 18. By 21, he was an Aviation Machinist's Mate Third Class at the Naval Air Station located on Ford Island in the middle of Pearl Harbor. Schleusner later recounted that on the morning of December 7th, everyone in his barracks was awoken by their commander telling them they were under attack, which was initially assumed to be a joke. But Schleusner quickly became aware of the reality of the situation when a bomb dropped on a hangar only a few buildings away. He had just made it down to the mess hall when the catastrophic bombing of the USS Arizona happened just 200 yards east of his building. Schleusner–along with everyone else at the Naval Air Station save one sailor on patrol that morning–managed to survive that day’s events.

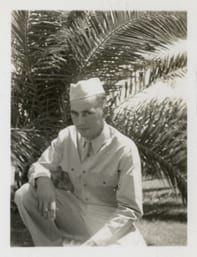

LeRoy E. Church, Church family collection, WVM Mss 2089

LeRoy E. Church of Lodi worked as an automobile mechanic for the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) enlisting in the United States Army Air Corps on November 18, 1940. Church arrived in Hawaii within a month of joining, and served first with the 23rd Material Squadron before reassigned to the 22nd Material Squadron a year later. He was with the Base Engineering Department at Hickam Field when the assault began, his barracks struck within the first few minutes of the attack. At the age of 25, Pvt. Church was one of 29 men in his squadron who lost their lives that day.

Lieutenant Rhoda Ziesler returning home in Hawaii from the Schofield Barracks hospital, December 9, 1941 after the December 7, 1941 attack. Rhoda Ziesler collection, WVM Mss 1914

Rhoda Ann Ziesler of Manitowoc, Wisconsin joined the United States Army Nurse Corps in 1940. Just weeks before the fateful day she was transferred from her training grounds at Camp Custer, Michigan to the 215th General Hospital located at Schofield Barracks in central Oahu, and was appointed head nurse of a 112 bed ward. While Schofield Barracks was not a primary target that morning, nearby Wheeler Army Airfield was. She later recounted her experience on an application for the Pearl Harbor Survivors Association, writing

On the morning of the attack, I and several other nurses were on duty and stepped outdoors to see what was happening. The Japanese planes were flying so low. We could see the rising sun [on the planes].

Ziesler remained at Schofield Barracks for the duration of the war, and afterwards married Robert Weller, a soldier and fellow Wisconsinite whom she had been reintroduced to while stationed in Hawaii.

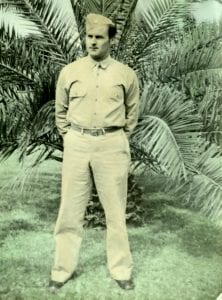

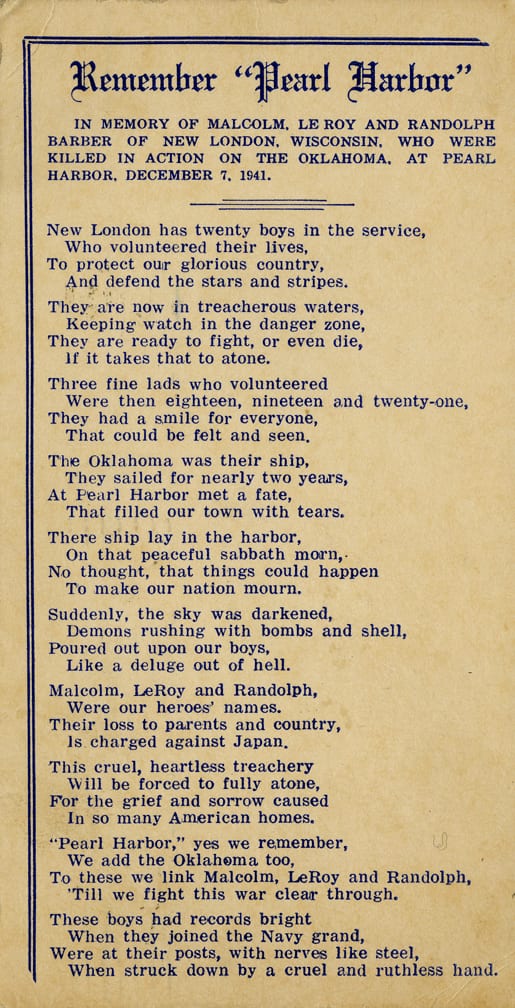

The Barber Brothers, Mss2012.082.

The Barber Brothers of New London, Wisconsin all enlisted in the United States Navy in 1940, 22-year-old Malcom and 19-year old Randolph following their 20-year-old brother LeRoy’s lead after he wrote from Great Lakes Naval Training Station to persuade them to join. In a break with Navy protocol, all three, now firemen, were assigned together to the USS Oklahoma. The Barbers were delighted they could stick together, but a couple of weeks before the attack, their father wrote the Navy asking that they be reassigned to separate ships. Tragically, the unthinkable still happened. All three brothers were trapped together when the Oklahoma capsized, their bodies never recovered. Two years later, the USS Barber, a Buckley-class destroyer escort, was named in their honor. (Note: On June 16, 2021, the Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency announced the identification of the remains of the Barber Brothers.)

The Barber Brothers poem, Mss2012.082.