A photograph of Akira Toki holding up his Superior Service Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs for his work at the William S. Middle VA Hospital. WVM.0854.I001.

In observance of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum presents the story of Madison area hero, Sergeant Akira R. Toki, who served with A Company, 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat Team during World War II. While Toki has been a notable figure for decades, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum is proud to re-introduce his story to the public through newly accessible oral histories of Toki, OH409 and OH886, now available online.

Akira Toki was born in Madison, Wisconsin, and lived with his family on a vegetable farm south of Madison, at the current site of the South Towne Mall in Monona. Toki graduated from West High School in 1935. The Great Depression negatively impacted his family, and they had to sell the family farm. They acquired another farm in an area by the Beltline Highway and the family moved there in 1936.

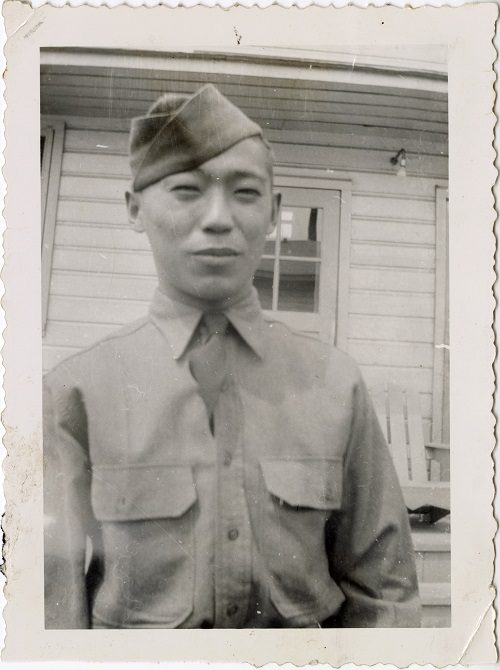

A photograph of Akira Toki during his time in military service. WVM.0854.I011.

On December 7, 1941, Pearl Harbor was attacked, and Toki received a draft notice shortly after. At the time, many Japanese Americans were being sent to internment camps, with the first of the camps being opened in California. Toki claims he had no knowledge of the camps at the time.

In February 1942, Toki reported to a building on East Washington Avenue and was inducted into the Army. Toki remembers that at the time, a Chinese American man was also being inducted. Here, Toki talks about the media interest in two Asian Americans being inducted at the same time:

TOKI: …They gave me a greeting card and told me to report to Selective Service. So--I reported and then I went to--they had us all meet uptown. If you know where Washington Building is up on the Square, it's an old--ah--it's a new state building up there. G.F. 1. [ Referring to G.E.F. --1, presently at 201 East Washington Avenue.]

VAN ELLS: One of them. I get them all mixed up.

TOKI: It's one, the first one. It was facing East Washington Avenue. So I rode up there and the Red Cross was there with donuts and coffee because it was 6:00 in the morning they told us to report back up there. Then--there was a Chinese boy that was inducted in the Army at the same time I was. You know what Chinese and Japanese were? We were enemies with each other but I didn't think nothing of it, you know.

VAN ELLS: Did he?

TOKI: No, no. I don't think he did either. The publicity that we got at that time, seeing a Chinese and Japanese inducted at the same time, the media kind of blew it out of proportion because they--saying two sides were inducted and armored at the same time.

VAN ELLS: So this made the papers?

TOKI: Yeah, made the papers. Made the front page. And they had us--they sat us in the bus, took pictures as we sat together in the bus, and all that.

After induction, Toki was sent to Camp Robinson, Arkansas, for nine weeks of basic training. Here, he was segregated into a small company with six other Japanese men. At the time, Toki felt that maybe their government did not trust them. After basic training, the white soldiers were sent off to their next duty, but Toki, along with the other Japanese men, were left behind in Arkansas. The group was deemed “unfit for combat duty” and was sent to Camp Grant, Illinois. Here, Toki describes his experience at Camp Grant with the other Japanese men:

TOKI: …Washington must have had a order out that they figured out we were unfit for combat duty, see. So they load us on a troop train from Camp Robinson, Arkansas, then they shipped us to Camp Grant.

VAN ELLS: In Illinois.

TOKI: Yeah. They didn't tell us where we were going. 'Cause they had the blinds all pulled, everything was hush, hush. So we didn't know what, where we were going, what we was going to do. We end up in Camp Grant. Then we--they divide us up into quartermaster and the medics and they were doing firemen duty. You know, firing the boilers in the barracks. And the reception center, 'cause I was in the reception center, pencil pushing.

VAN ELLS: Yeah. And so they had basically turned you into permanent party at Camp Grant.

TOKI: Yeah, as non-combatant duty, see.

VAN ELLS: How long did that last?

TOKI: About a year and a half, I think.

VAN ELLS: And what did you and the others think of it? I mean, did you want to get out there?

TOKI: A lot of us bitched and moaned and hollered 'cause we saw, you know, a lot of the cadre were, Caucasian cadre, and they were taking troops out--recruits out to other camps and then coming back and doing that kind of stuff and we were just stuck there. So I used to complain and crab and bitch and holler why we couldn't do that. But, you know, when they say we're unfit for combat duty and we're not trusted--that they took all of our weapons and everything away from us, we didn't have nothing. Just, just nothing. Just our clothes, that's all we had. So we--I went to the commander. I think I did the most bitching of them all 'cause, you know, when I live around all the Caucasians and I think I feel like I'm equal to anybody else, see. But then I think the first thing I knew, to shut me up, they sent me on a furlough. So my furlough, from Camp Grant to Madison [both laugh]--

VAN ELLS: Madison, right.

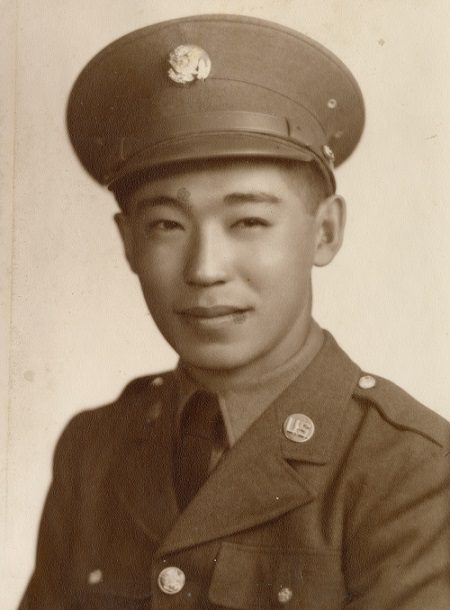

A photograph of Akira Toki in his uniform. WVM.0854.I016.

Toki spent a year and a half doing clerical duties at Camp Grant and was eventually promoted to corporal. He was then assigned to Camp Blanding, Florida, where he served another year and received advanced infantry training. He became a squad leader during this time. Toki spent a total of two and a half years serving stateside with the segregated group of Japanese American men.

Eventually, Toki was ordered to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, where the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was organized. This group was a segregated Japanese American unit. Toki joined this group and the unit trained together before being sent to Camp Patrick Henry, Virginia, in April 1944. Here, they would embark on a ship to Europe to join the war effort.

A photograph of Akira Toki's unit, part of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, in Italy, 1945. WVM.0854.I013.

Toki landed in Naples, Italy, which had recently been through a bombing. He was assigned to A Company, 100th Infantry Battalion, which was composed of almost entirely Japanese American soldiers. Toki was a squad leader in A Company. After some time, Toki’s unit was tasked with rescuing a lost battalion of 275 men that were surrounded by German soldiers. Some of his unit performed a bayonet charge against the enemy. Toki’s unit sustained heavy casualties. Here, Toki describes receiving the order and rescuing the battalion:

TOKI: Then -- then we got called up again for the Lost Battalion, the 36th Division, Texas division, was the regiment was trapped, they were surrounded by the Germans, they couldn't go backwards, forwards, or nothing. And -- and we were under strength, we were down real low at that time, but they called us up and told us to go get them. So we, I think we were supposed to be resting for five days getting our replacements down, but they told us we need you, so they took us they called us back in about five days time, we were called back up to the front line again. And we -- and they, they told, the general told us we were supposed to get those guys out in a week's time and we dug them out of there in five days. And it was -- in a place where you had to use shrubs and stuff to hang on to climb up the hill. It was a rough, rough terrain where we were, and the Germans had, you know, they had their guns emplaced in the right positions so every move we made they could see us, see. So we, we got those guys out in that length of time.

DERKS: How did you do it? How did you get them out?

TOKI: Well, toward the end a couple of the company did a bayonet charge, they went gung ho and went charging up the hill with the bayonet, but like some of the companies out of that Lost Battalion, us guys we only came back with one guy in the whole company. That's how high the casualty was, and like in my company we had 21 guys left in our whole, of 200 guys, and I was in charge of a squad, I came back with one man. . .

For the rest of his service in Europe, Toki experienced heavy combat. He fought through Italy and was part of the Po Valley Campaign, codenamed Operation Grapeshot, in April 1945. This campaign saw the Allies pushing against the German line, fighting them back further and further. During combat, Toki was hurt and was awarded a Purple Heart. Toki was recuperating in a hospital during V-E Day on May 8, 1945.

Toki remained in Europe for the rest of the year and returned home to the United States shortly before Christmas in 1945. Toki was discharged from the Army at Fort Sheridan, Illinois, and returned home to Madison, Wisconsin. He got married and continued farming on the family farm. For over fifty years, Toki volunteered at the William S. Middleton VA Hospital and was a member of numerous veterans’ organizations.

In 1993, the Orchard Ridge Middle School in Madison was looking to rename their school. Toki remembers how local children began a campaign to get the school named after Toki:

TOKI: How Toki Middle School got started? Well, at that time, there were five schools buildings, were had -- graded school, integrated with, middle school, see. And they wanted to separate them, so Orchard Ridge was one of them, and Hamilton was another one, and there were a couple other ones. I can't remember anymore. But the reason they selected me, because they were looking for minority people, names. They wanted, they were selecting like White Horse, or Ray Charles, and all those kind of people. But the, our chief Volunteer Service person, who worked at the VA hospital, his kids were going to school, see. And he's, he kind of instigated that they should pick my name.

TOKI: So they did research on it and the kids did all the work. They started from, from class, they made the resume of the school name. And then they presented to the school board, the PTO, the board of education. It went up, all the way up the line. And then went to the city. That's how it got started, the kids, the kids did the research. Parents didn't have nothing to do with it. The eighth grade kids did it all.

DERKS: Was there a ceremony, a naming ceremony?

TOKI: Yeah, yeah, yeah, they had a party. So, I go back there every once in awhile, and talk to the kids.

Today, the Japanese American 442nd Infantry Regiment is known as the most decorated regiment in U.S. military history. During his service, Toki’s battalion earned multiple Presidential Unit Citations. Toki himself received three Bronze Battle Stars and a Purple Heart. Toki was interviewed by the Wisconsin Veterans Museum in 1996 and by Wisconsin Public Television in 2002.

Akira Toki passed away at the age of ninety-six on June 29, 2012. For the first time since he was last interviewed, Akira Toki’s oral histories are now fully available online with transcripts. Objects and information from Akira Toki’s Collection is also available online by clicking here.

For the full February 12, 1996 interview with Akira R. Toki and Mark Van Ells, click here.

For the full September 3, 2002 interview with Akira R. Toki and Mik Derks, click here.