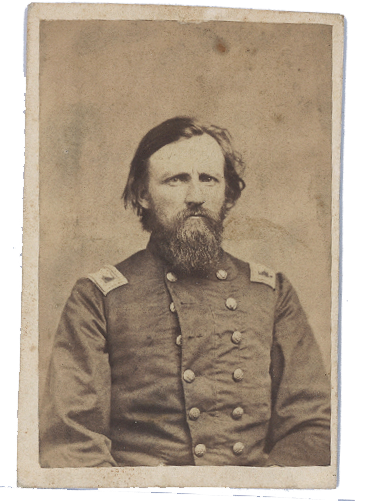

Unpublished photo of Colonel H.C. Heg (courtesy of The Robert Drane 19th Century Photography Trust).

Have you ever noticed, amidst the festivities of a Farmer’s Market Saturday on Madison’s Capital Square, the moment when visitors come upon the statue of that soldier on King Street – a young man in uniform, standing tall, eyes fixed on the horizon, somehow intent on moving forward on behalf of the flag fluttering in the distance over his left shoulder?

His presence prompts an interlude of silence and curiosity. Who is he; why is he here; what message does he wish to deliver to those who stop and ponder his eternal presence?

He is a soldier who gave up his life that our nation might live.

He could be many soldiers from many wars, but in this case he is Hans Christian Heg, proud son of Norway, and Colonel of the 15th Wisconsin Regiment on August 19, 1863, the day he fell in battle at Chickamauga, along the “river of death,” down in Georgia.

He was 32 years old on that day, with a wife and three children praying for his safe return, up North in the small town of Waterford, county of Racine, Wisconsin.

As he led his regiment across a small stream at the southern end of the battlefield, he was struck in the gut by a Confederate minie ball that seared his body and shocked his limbic brain. Perhaps his life flashed before him in that instant.

His joyful boyhood in Lier, Norway, three miles to the north of the port city of Drammen. At age eleven, in 1840, the journey across the Atlantic from Oslo to New York, then from Buffalo through the Great Lakes to Milwaukee and on to the Norwegian settlement near Lake Muskego, in Racine County, founded in 1825. There a lovely 350-acre farm.

A new language to be mastered, along with many lessons in community from his father, Ewen, whose famous “Heg Barn” became the gathering place for social and religious events, and whose journal, Nordlyset (Northern Lights), was the first Norwegian newspaper in America, and later an organ of the Free Soil and Republican parties.

At age twenty, a rite of passage. Hans and three pals bitten by the gold bug, navigated the perilous journey to California and spent two years as Forty-Niners. This lark ended when Even Heg died, and Hans returned home to his roots in Muskego.

Next came the love of his life, his beautiful bride, Gunhild Einong, and the joys of three offspring, little Hilda, James and Elmer.

Followed by recognition, for Hans, like his father, proved to be a natural-born leader. He became Major in the 4th Wisconsin State Militia. A public person, board of supervisors in the Town of Norway, delegate to the Republican Convention of 1857 in Madison, Wisconsin State Prison Commissioner at Waupun in 1859.

All was working out nicely for Hans Heg and his family. Fine prospects for a long and satisfying life and a happy ending. But, as Lincoln put it, “then came the war.”

Governor Alexander Randall appointed the popular Heg, Colonel of the 15th Wisconsin Volunteers as of September 30, 1861. His first duty was recruiting, which brought this appeal:

“Scandinavians! Let us understand the situation, our duty and our responsibility. Shall the future ask, where were the Scandinavians when the Fatherland was saved?”

After winter training at Camp Randall, Heg led his 960-man contingent into the field. Indeed they were Norseman – Olsen, Hanson, Peterson, Johnson, Thompson, Erickson, and no fewer than 115 who answered to the name of Ole. They marched off in companies: the St. Olaf Rifles, Scandinavian Mountaineers, Heg’s Rifles, Rock River Rangers, Clausen’s Guards.

What followed is what always follows in war. Drums beating the long roll, the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange mournful mutter of the battlefield. In October 1862, the Scandinavian Regiment skirmished at Perryville, Kentucky, followed on December 31 by a terrible slaughter at Stones River, as Heg’s regiment, along with his entire Union corps, was overrun by the CSA left wing, under Braxton Bragg. A hellish day, bitter cold, running through the woods, firing, killing and dying. After a Union rally and stalemate, Heg wrote:

“There is no denying that we were badly whipped the first day, as usual because of an infernal fool of a General allowing himself to be surprised. We lost a great many men.”

A charcoal portrait of Hans Heg from the WVM Collections.

A charcoal portrait of Hans Heg from the WVM Collections.

A total of 138 men, with 15 dead in his regiment alone. But Heg received a commendation from General William Carlin, as “the bravest of the brave.”

The following September, the blue army snaked further South, eager to attack Bragg again, below Chattanooga. Heg now commanded the entire Third Brigade, and he wrote a final letter home on September 18, 1863:

“The Rebels are in our front and we may have to fight him…in a big battle. Do not feel uneasy for me. I am well and in good spirits and trusting to my usual good luck. I shall use all the caution and courage I am capable of. Good-bye my darling.”

Toward sundown the next day Heg’s luck ran out. He was leading a Union counter attack near the Viniard House when he felt the lead ball slice through his lower bowel. It was a grievous wound, and he suffered all night before succumbing mid-morning on the 20th.

Chickamauga had been the “big battle” Heg predicted, with 35,000 men lost between the two sides, a number topped only by the 58,000 casualties a month earlier at Gettysburg.

When the war ended 18 months later, the Scandinavian Regiment numbered 320 survivors out of the 960 who marched out with Heg.

And so the story appeared to end in despair. But not quite – for Heg’s Norwegian community assumed the duty of remembering him and the men he led.

On October 17, 1929, “St. Hans Day” in Norway, Heg rose again in the magnificent statue on the Square, crafted by sculptor Paul Fjelde. Dignitaries such as the Governor and Mayor turned out, but the occasion belonged most to attendees from back home, the Colonel’s daughter, Hilda, and four octogenarian comrades from the old 15th.

In remembering him that day, they honored him. A soldier who gave up his life that his nation might live. Some 185 years later, it is only right and just that we too pause at the King Street corner, and do the same.

“The Statue on the Square” appeared in the 2014 Summer issue of The Bugle, a quarterly newsletter that is an exclusive benefit of WVM membership. To read more stories like this, become a member at https://bit.ly/1hj93YR