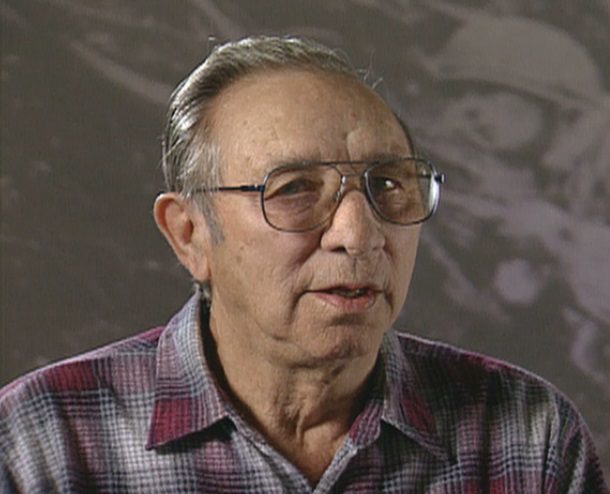

In this blog post, Urban A. Sippel of Glenbeulah, Wisconsin, retells his story with the 1st Special Service Force (1SSF) during World War II in Italy, from November 1943 to June 1944. He supplies a detailed account of the 1SSF at the Anzio beachhead and later breakout as part of the Fifth Army.

The joint American and Canadian 1SSF trained in Helena, Montana, drilled in unconventional tactics and warfare and was the forerunner of the United States Army Special Forces. The unit did not train like other units in the United States military.

First Special Service Force shoulder sleeve insignia. WVM.K1971.648.

Instruction included fighting styles taught by police officers from Hong Kong, learning how to fight to win with hand-to-hand combat coached by World War I veterans, running for sixty miles, filling your ruck full of rocks and running up a mountainside, parachute operations, skiing, winter operations, and intentional sleep and food deprivation. Also, as Sippel recollected, the traditional enlisted-officer relationship varied from that of the conventional Army.

Just before redeployment to the Anzio Beachhead, the 1SSF participated in Operation RAINCOAT and the Battles of Monte la Difensa and Monte la Remetanea between December 3 and December 9, 1943. These battles appear in the 1968 movie, The Devils Brigade.

Sippel recalls mountain climbing for tactical reasons at night and fighting the Germans in the mountains:

SIPPEL: Where we didn't go a routine. I mean, but our biggest traveling was at night, in the mountains. We would go to this mountain and then you'd pick your path where you're going to go to the next one, going up. And then during the night you would go to the next mountain. And we were quite a spearhead outfit because, like, where we were, there was a valley between this, that big mountain, and we'd go up and then we'd come down the mountain, down the face of the mountain and cut off the Germans. And then the infantry would come up the-- through the valley. That's where-- that's probably the biggest thing we did.

INTERVIEWER: So, they drove them right up the valley toward you?

SIPPEL: Until-- Well, we'd cut 'em off and then they would come up there. And then we'd go back up the mountain, take the next one. This is what we did.

INTERVIEWER: So, how do you climb up or down the mountain at night?

SIPPEL: You pick your way real good during the day. We stayed at the top of the mountain and then you picked your way. I mean, we didn't always-- everyday we'd get the next mountain. But whenever we had to move, that's when they told us we had to move, that's when we went to the top and picked our way which way we're gonna go up. And after we got past this one mountain where they had the sixteen-inch gun, when they knocked that out, then we came back-- well, I came back and I had pneumonia when I came off the front.

At Anzio, in early February 1943, and following the initial landings of Operation SHINGLE, the 1SSF would replace the devastated 1st and 3rd Ranger Battalions on the allied right flank from the beach inland along the Mussolini Canal. The 1SSF continued to use unconventional tactics against the Germans, including psychological warfare. But, given the difficult situation at the Anzio Beachhead, the 1SSF found itself in trenches and a more conventional war-fighting role:

INTERVIEWER: Yeah, tell me about Anzio.

SIPPEL: That-- well, that-- It was flat country. They had drainage ditches in there. Some big ones, some small ones. We were on the southern end of it, from the ocean out. We were on-- that was perfectly flat. But we were behind the ditch. We were there quite a while. We were dug in. In fact, we had foxholes where we could sit in. Well, you made it where you could sit in and then one guy slept on each side. And we had covers over the top, because they strafed us a lot. We had covers over the top.

INTERVIEWER: They strafed you? The airplanes would come over and strafe you?

SIPPEL: Yeah. Yeah, we had one-- every once in a while, he-- you never knew when he was coming. But, I mean-- and they would come real low. They would come maybe, maybe twenty-five to thirty feet up in the air and strafe us. So, if we-- anybody heard it, everybody went and made sure you were duckin'. That one-- that one we finished him off because one time he strafed, and he strafed our hospital, and that's when we decided we're gonna get him. We did. Everybody sat with a rifle and when he came over, everybody shot. And that did it. We knocked him out. He never came after that. It must have been just one guy that came.

INTERVIEWER: It was okay for him to strafe you and shoot at you, but once he went for the hospital, then you were gonna get him. [Laughs]

SIPPEL: That was it. There was no more of that. Hospital was important to us, you know. [Laughs]

INTERVIEWER: You'd think having somebody strafe you would be a bit annoying, too.

SIPPEL: The thing is the hospital had no protection. It was just in tents. So, I mean, that-- yeah.

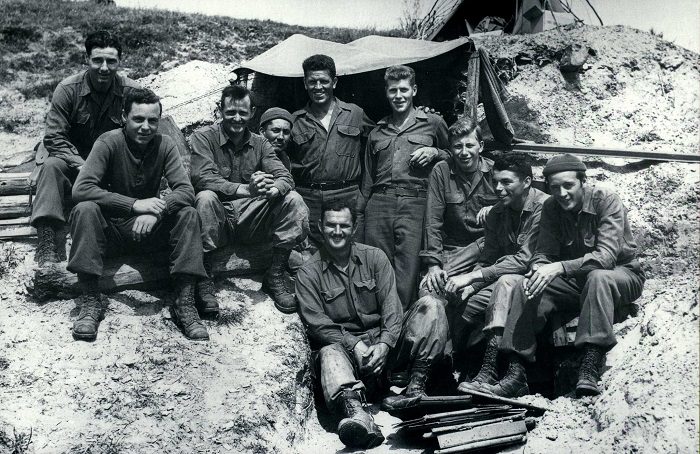

Members of the elite American-Canadian 1st Special Service Force created strong ties among the men and their respective nations while serving in Anzio, Italy, in 1944. WVM World War II Prints Collection, Lithograph, WVM.3043.

Sippel's German ancestry gave him an edge while fighting Germans in World War II. Soldiers of the 1SSF would leave stickers on German soldiers indicating their presence in the area.

At Anzio, the Germans dubbed the 1SSF the “Black Devils.” There is no record of any German ever referring to the 1SSF as “The Devil’s Brigade.” The Germans referred to 1SSF soldiers as “black” devils because its members smeared their faces with black shoe polish for covert night operations.

Here, Sippel remembers one such night raid at Anzio:

INTERVIEWER: How did it help you to speak German?

SIPPEL: Because I could hear when the Germans were talking and I knew what they were saying. [Laughs] After I talked to-- well, when we got prisoners, I talked to them, and they talked just like my grandpa. It was just, hey. Actually, it was easier for me to get along in Italy because all the kids knew German. They had to learn German. Now, that German I could understand, that they learned. But the High German, that wasn't my thing. We went up one night, we were supposed to-- well, they figured they had an outpost in a building, so three of us went and we got caught. There was an intersection there and a two-story stone house sitting there. We were going and all of a sudden, hoop, they threw up a flare. And we were between the house and the road. And they shot over our head and threw mortars at us. And they kept-- The guy in front of me, he says, "Every man for himself!" So, when the flares were down, we took off and went back. Well, that was what we wanted to find out, where their outpost was. And it was in that stone house. So, we went back and told. But they had machine guns. It was a crossroad and they had machine guns sitting on the other side of the road. And they were shooting. We were lucky we were lower down. They were shooting over our heads. So, when we went back, that's where our training was something because you have-- I mean, when they shoot up a flare, you could hear it when they would shoot it. Then you have so many seconds and then it opens up. So, that's the time you had to move, in between that. We went back, and when we got back, we told 'em what we hit. They said, yeah, they could see it from the frontline. The next night we went-- well, one guy caught a mortal shell on his leg, a dud. It bruised his leg. So, the next night, one guy took a bunch from the opposite side of that one road. I was on the other side, and we led 'em up and they blew up that house. Demolition went in, and what was really funny is, when they said, "fire in the hole" and they came out, here there was a guy upstairs with a flashlight sending signals. We went right back then, as soon as it blew. Well, when it blew, we were on our way back already. The next day, that two-story stone house was just a pile of rubble. We were wondering what happened to the guy up there sending signals. [Laughs] Which, you know, it was something to laugh about. But I mean-- Shortly after that, then we-- we went from there, we headed towards Rome.

Sippel and the rest of the 1SSF participated in the Anzio breakout in late May 1944. On May 30, 1944, mortar shrapnel injured Sippel while trying to take a nap a few days before 1SSF entered Rome. He received the Purple Heart because of his injuries.

Later, after refitting, the 1SSF went on to invade southern France in August 1944, on the islands of Port Cros and Île du Levant. The Army attached 1SSF to the 1st Airborne Task Force and saw action in the French Riviera.

On December 5, 1944, the United States military deactivated the First Special Service Force (1SSF) in Menton, France.

A Menton Day challenge coin.

Ironically, to the present day, United States Army Special Forces and affiliated Canadian soldiers celebrate December 5, known as Menton Day, with airborne operations, parties, displays, exhibitions, and military balls. United States Army Special Forces trace their lineage to the 1SSF, and Sippel's story reflects their mindset and fortitude. In 2015, the 1SSF, received the Congressional Gold Medal for their actions in World War II.

Following deactivation, the First Special Service Force disbanded, and the Army reassigned Sippel and many of his peers to 3rd Battalion, 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment (PIR), 82nd Airborne Division. The Army then sent him by train to northern France.

To learn more about the relationship between these former First Special Service Force soldiers and the soldiers of the 82nd Airborne Division, click on the image below and go to time stamp 00:58:00: