PART 1: Prelude to the Ground War: Mobilization, Deployment, and Waiting

On 24 February 1991, after 40 consecutive days of around-the-clock aerial campaign, the ground offensive phase of Operation Desert Storm (code named Operation Desert Sabre) began at 4am Saudi time.

Over the last six months this final, and perhaps inevitable, assault loomed on the horizon for the nearly one million coalition forces gathered in the region. Practically every continent was represented in the largest international coalition since World War II. The United States committed over 650,000 service members to the endeavor – two-thirds of the entire international force. Units from across the country mobilized and deployed in support of the operations. Wisconsin was no exception.

An estimated 10,400 Wisconsin men and women mobilized for the conflict. In addition to those Wisconsinites on active duty in all branches of service, for the first time since 1961 members of the Wisconsin National Guard from across the state were called up, as well Reserve units including these listed below.

Some units were activated to backfill positions state-side or overseas, while many deployed to the region during the six-month build-up during Operation Desert Shield. Thousands staged and departed from Fort McCoy and Volk Field in the fall and winter of 1990 to 1991.

The weeks and months before the ground offensive were full of training, waiting, and adapting. The environment of the region required just as much adjustment as anything else. Leslie Achterberg, of the 1122nd Transportation Detachment out of Madison that arrived in Saudi Arabia in October 1990, described the conditions in the sands and sun of the Saudi desert.

This pace is not too bad, now that we’ve been her for eight days. The temperature is falling a little now. It has only been getting up to 100 degrees during the day, but down to 75 at night. Not too bad considering the day we arrived it was 120 degrees.

For those units that didn’t deploy until several months later like the 13th Evacuation Hospital out of Madison, the weather was completely different. Expecting the desert heat, Lewis Harned, of Madison, commander of the 13th Evacuation Hospital, remembered the dramatic difference in climate.

“It was interesting, when we first got over there in January, when we set up it was cold. We had frost; the water in the washbasins every morning were frozen. It was cold. And then, all of a sudden, it started to warm up. The last week that we were there, it was temperatures – every day 130, and we’d get down to 100 at night, but dry heat. Extremely dry heat.”

Helen Gurkow, a doctor with the 13th Evacuation Hospital

Elements of the 13th Evacuation Hospital arrived in Saudi Arabia amidst active combat on the day the air campaign began. The threat of a Scud missile attack was ever-present, especially at night. Helen Gurkow, a doctor with the 13th Evacuation Hospital, remembered the first days after their arrival were full concern and fear.

“…that was when we knew we were in a war. And sometimes I can’t even talk about it unless crying because it was so frightening… Saddam was really smart because he always scudded us at night. It was frightening enough anyway. And so you would just get ready to go to sleep, or you’d get to sleep and then about ten or eleven o’clock you could faintly hear the sirens at the airport and then somebody would be driving around the compound with a loudspeaker, 'SCUD ALERT, SCUD ALERT!' And so then we would get MOPP 4 [Mission Oriented Protective Posture, Level 4]. And MOPP 4 of course was everything: chemical suit, boots, gas mask, helmet and gloves."

Doral Clark from Lodi who served with a Wisconsin National Guard hospital unit recalled,

“When the [air] war started I was still in Daharan [Saudi Arabia] and we had a whole bunch of Scuds in. We wore gas suits which were like a heavy snowmobile suit, about comparable to a snowmobile suit and they were filled with charcoal, and we had gas masks, and hoods that we had on and gloves, and rubber boots. When it’s a hundred degrees that’s a little uncomfortable, to be dressed that warm.”

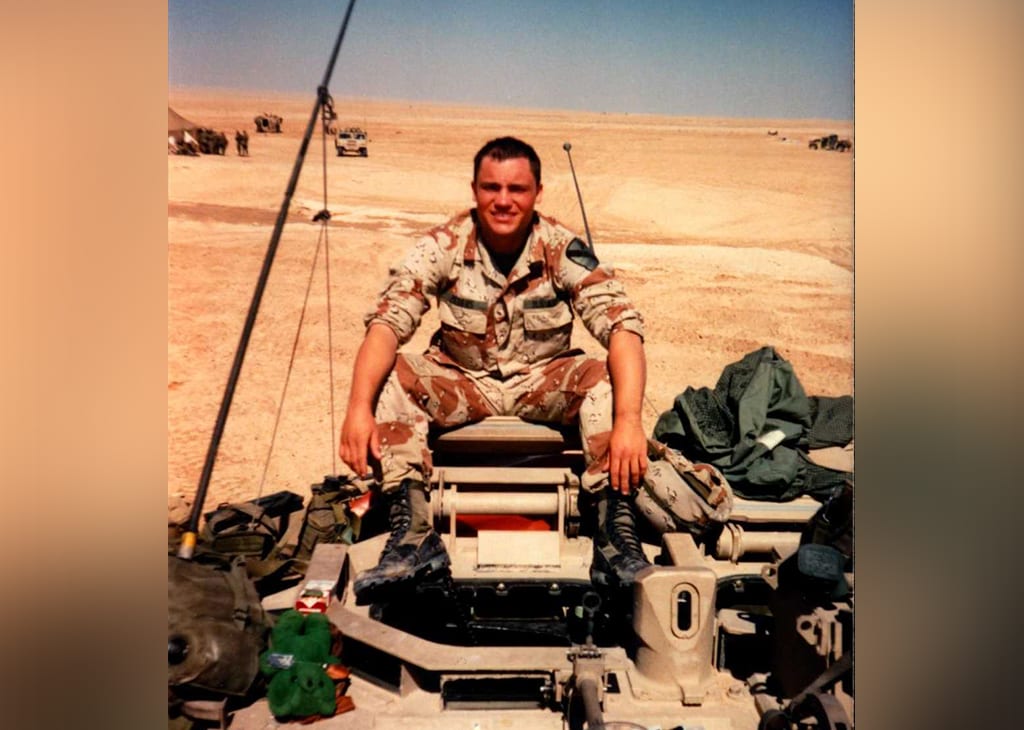

John Peters, of Merrill, Wisconsin, served with the 1st Cavalry Division

John Peters, of Merrill, Wisconsin, served with the 1st Cavalry Division along the border with Iraq from just after New Year’s Day 1991 to the beginning of the ground war. Peters remembered the feeling in the days leading up the beginning of the ground offensive.

“I think at that point we were getting frustrated. You’re bored. Because you’re on the border, you’re not doing any kind of training so that was kind of one good thing. I’m tired of training. You’re just sitting on the border and you’re always got a guy in the turret [of the Bradley Fighting Vehicle], scanning with the thermal sights – twenty-four seven. You’re sitting around, doing nothing. It gets old. I think I was like, ‘what’s going to happen here?’ It got to the point where it’s like, ‘hey, let’s get this over and done with.” We were sitting around and supposedly they were going to invade Kuwait much earlier on, start that air campaign, but they wanted to bring in more troops. They brought in these division out of Germany. ‘Jeez, how many troops do you need here? My God, you got what – over a million? I know Iraq has got a lot but their equipment sucks.’ It was just frustration. ‘How long is this going to take?’ We figured, ‘Air war, two weeks, they’ll wipe them out and we’ll just come in there and clean up the mess. Mop it up.’ It went longer than expected – so just frustration.”

Jeffrey Coonjohn, with the 826th Ordnance Company out of Madison, recalled later,

“By the middle of February, Coalition ground forces were poised and ready to strike. The wettest desert winter in over twenty years continued to plague our operations as well as those of the combat units. Still, no attack orders arrived and everyone waited. Air sorties had exceeded 80,000 by February 18th and estimates of Iraqi war dead were rumored to be approaching 100,000. To date, less than 100 American soldiers had been killed in action, although the ground war was expected to dramatically increase this number. While the waiting war dragged on, I continued to work.”

Lewis Harned, of the 13th Evac Hospital, remembered the stark reality of what they were preparing for on the eve of the ground campaign.

“Our unit was with the VII Corps…Each corps had five MASHs [Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals], five combat support hospitals, five evac hospitals…We had over 600 beds for casualty. And we were told prior to ground war they had no idea what was going to happen, but we could expect 5,000 casualties a day.”

On the eve of battle, emotions were high; fear, frustration, and anticipation. No one ever knows exactly what tomorrow will bring. All you can do is prepare for it the best you can and be ready to adapt.

Be sure to follow us for Part II as we mark the 30th anniversary of the "100-hour war" with more Wisconsin stories from the Persian Gulf.