In 1945, 75 years ago, World War II in the Pacific ended with the Battle of Okinawa and the atomic bombing of Japan. These important events, in which Wisconsin service members did their full duty, still impact the world today.

From April until August 2020, the Wisconsin Veterans Museum staff will explore World War II’s end, highlighting materials and stories of Wisconsin veterans in our collection. Follow the links in the post to explore related collections and more Wisconsin stories.

Okinawa: The Battle Builds

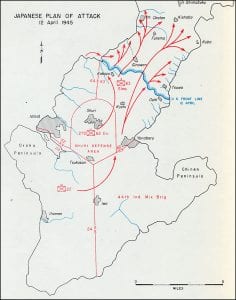

As April 6th dawned, Tenth Army was ashore and advancing on all fronts. “All units are doing splendidly,” recorded General Buckner. But the lull of the last few days would end rudely on this day, as the Japanese response, codenamed Ten-Go or Heaven Number One, got underway.

At midday the Fifth Fleet endured its first mass Japanese air raid as over 400 aircraft arrived from Kyushu. Over half were kamikaze planes—suicide attackers. The Japanese called these large attacks Kikusui or Floating Chrysanthemum. The First Floating Chrysanthemum sank or damaged seventeen U.S. ships, while repeat attacks (the Second and Third Floating Chrysanthemums) on April 12th and 16th added to the grim total. Over the length of the campaign, an average of ten kamikazes per day crashed into the fleet, sinking thirty-six Allied ships and damaging 386 more.

The Japanese Navy also sent its most powerful battleship Yamato, south from Japan to fight her way to the Hagushi beaches. Escorted by one light cruiser and eight destroyers, the ships had enough fuel for a one-way trip. U.S. submarines detected the force on the evening of April 6th. At 12:30 on April 7th, the first of several air attacks from Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher’s Task Force 58 swarmed the Japanese ships. Yamato battled for nearly two hours of fierce combat before capsizing and exploding. The cruiser and four destroyers also sank, while the remainder turned back for Japan. This action effectively finished the Imperial Japanese Navy as a fighting force.

Ashore, the 6th Marine Division advanced into northern Okinawa. For ten days, the Marines encountered little more than isolated snipers and roadblocks. On April 13th, they found the bulk of the area’s 2,000 Japanese defenders dug in on the 1,400-foot Mount Yaetake. The Marines surrounded the mountain and started attacking upward, assisted by airstrikes and naval gunfire. The mountain was captured on April 20th, with few defenders escaping death. These Japanese fugitives would harass troops in northern Okinawa into July.

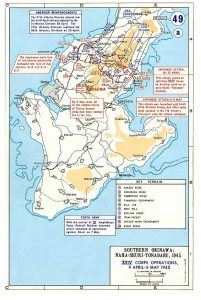

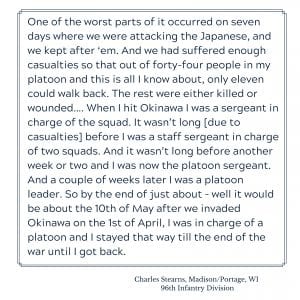

Further south, XXIV Corps fought through Ushijima’s outposts and encountered the first main defense line before Shuri. The 96th Infantry Division faced Kakazu Ridge, while the 7th Infantry Division found a series of ridges topped with bunkerlike stone Okinawan tombs. Both divisions attacked repeatedly but failed to make much progress against fierce Japanese fire and counterattacks. On April 12th, after three days of fighting, the corps had advanced no more than 500 yards and paused to regroup.

“It is going to be really tough,” said General Hodge. “I see no way to get them out except blast them out yard by yard.”

Sensing an opportunity and spurred by a message from Tokyo, Ushijima ordered a counterattack. On the night of April 12th, over 3,000 Japanese attacked XXIV Corps, intending to infiltrate and cause an American retreat. Machine guns of the 7th Infantry Division stopped the Japanese in front of them cold, but in the 96th sector the Japanese reached the positions facing Kakazu Ridge. Ships offshore fired illuminating starshells that turned night into day while Americans and Japanese fought savagely. In the end, the Japanese withdrew and conceded defeat. Over half of the attackers lay dead on the field.

Beauford T. Anderson, 96th Infantry Division, of Eagle River, WI, earned a Medal of Honor for his heroic actions on the night of April 12-13, 1945 on the slopes of Kakazu Ridge. Anderson (center) is photographed here after the battle with souvenirs from the fight. Photo: U.S. Army.

Two deaths overshadowed these battles. On April 13th, the Americans learned of the death of President Franklin D. Roosevelt at Warm Springs, Georgia. Five days later, famed war correspondent Ernie Pyle was killed on Ie Shima, a neighboring island, as he covered the 77th Infantry Division’s invasion of the place and capture of its key airfield.

Meanwhile, General Hodge brought up the 27th Infantry Division as reinforcements and renewed the attack on April 19th. Land-based artillery joined with naval gunfire to open the offensive, in the largest bombardment in the Pacific War. The massed firepower had little effect on the sheltered Japanese, who greeted the Americans with their usual ferocity. Ushijima’s defenders held off Hodge’s attackers in five days of back-and-forth fighting, until growing casualties caused Ushijima to order a retreat southward.

Admiral Nimitz and his commanders worried about the slow progress ashore, especially as kamikazes continued to take a toll on Fifth Fleet’s ships. Nimitz visited Okinawa on April 23. “I’m losing a ship and a half a day,” he told Buckner. “So if this line isn’t moving in five days, we’ll get someone up here to move it so we can get out from under these damn kamikaze attacks.” XXIV Corps continued its push into the next layer of the Japanese defenses.

A few days later, Buckner decided to send the 77th Infantry Division and the entire III Amphibious Corps to southern Okinawa. Once these units were in position, Tenth Army would launch a major offensive in May. Little did Buckner know that at the same time General Ushijima was planning an offensive of his own for early May.