Old Abe, an icon in Wisconsin Civil War history was an American bald eagle who served with the Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment. He participated in over 30 battles, narrowly avoiding wounds on several occasions. During the war, he became a rallying point to Union troops and an anathema to Confederate soldiers, who set bounties on the "Yankee Buzzard." His service to the Union resulted in widespread fame, and his life after the war reflected the esteem with which Wisconsin and other states held him.

Early Life of Old Abe

Ah-Ga-Mah-We-Ge-Zhig1, or Chief Sky and Old Abe

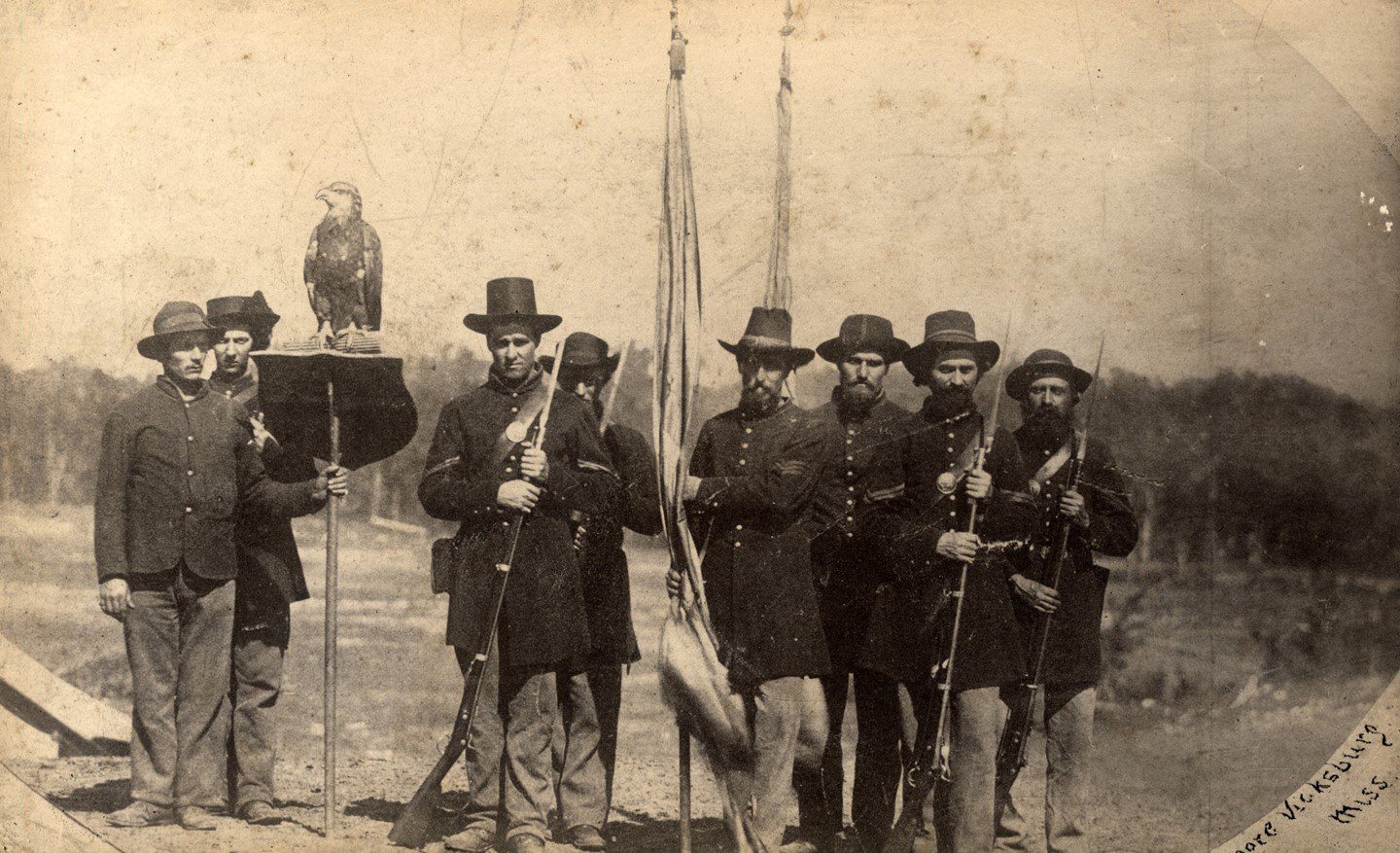

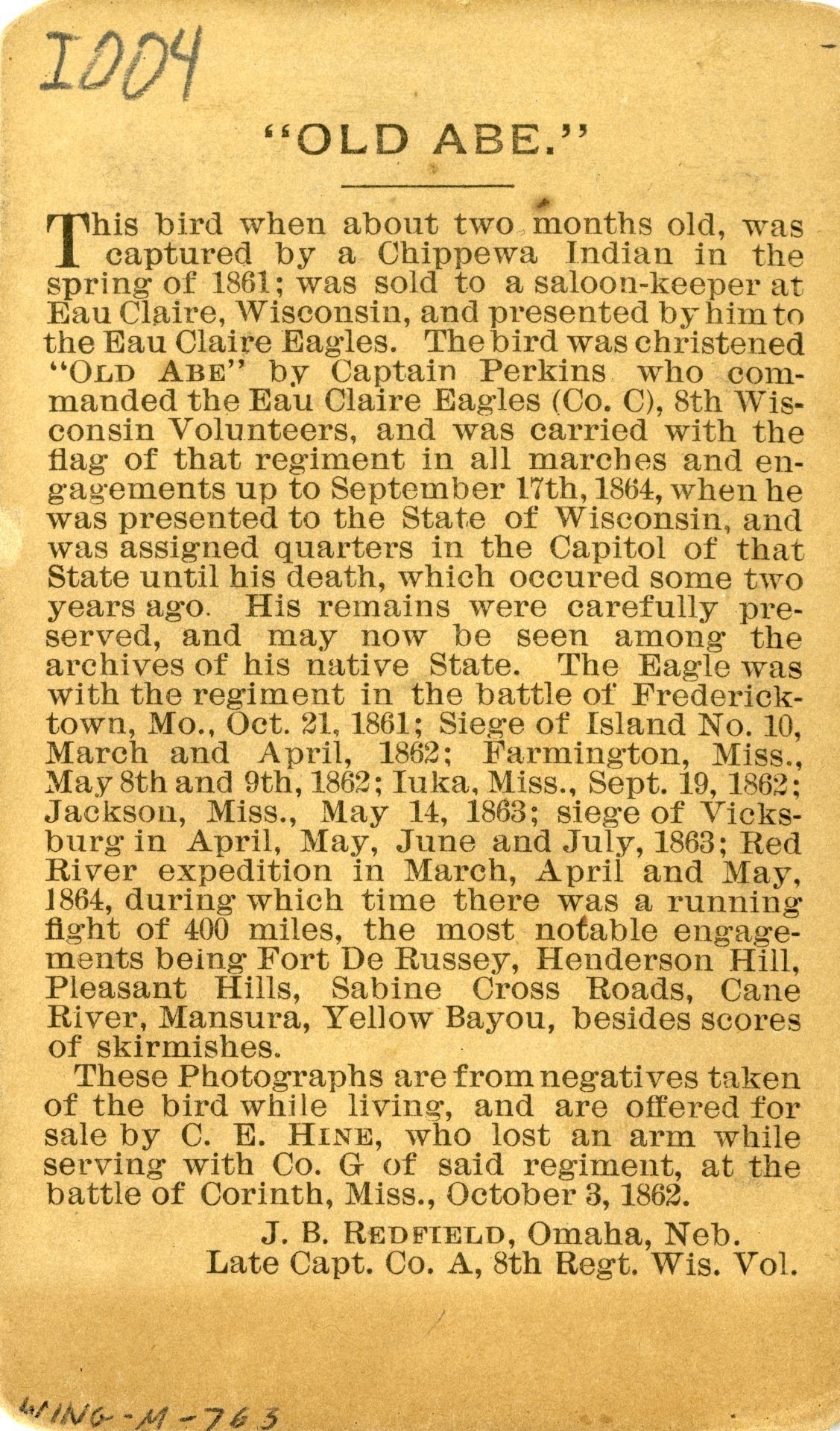

The bald eagle who would gain fame across the country as Old Abe spent almost all of his life in captivity. In 1861, when only a few months old, he and a hatch mate were taken from their nest by Ah-Ga-Mah-We-Ge-Zhig1, or Chief Sky, a member of the Ojibwe (Chippewa) of the Lac du Flambeau Band. He later recalled the location of the nest where the eagles were found for J.O. Barrett, who wrote the first biography of Old Abe. According to Ah-Ga-Mah-We-Ge-Zhig, it was “in or near Town 40 North, Range 1 East, four miles from [1865] eastern boundary of Chippewa County.”

The exact method of the capture varies slightly among several sources. One account states that, after noticing a mature bald eagle hovering around a tree, “one of the Ojibwe men climbed the tree to the nest and while up there the old eagle charged on him and had to be shot.” Another explanation has the tree containing the nest being cut down by Ah-Ga-Mah-We-Ge-Zhig, after he shot a mature eagle, presumed to be the mother of the two eaglets. Only Old Abe survived this extraction—his hatch mate perished soon after.

Ah-Ga-Mah-We-Ge-Zhig later traded the surviving eaglet, for a bushel of corn, to Margaret McCann in the tiny community known as Jim Falls, Chippewa County. McCann’s husband, Daniel, had difficulty walking due to a childhood accident and wanted to contribute to the war effort in some way. Upon hearing of the formation of a militia company in the Chippewa Falls area, he decided to offer the young eagle as a mascot. The Chippewa Falls men refused the offer, but a company from Eau Claire agreed to purchase the eagle for their mascot.

A Mascot Named for a President

One of the men from the Eau Claire company, Lt. James McGuire, approached the unit’s captain, John E. Perkins, and asked permission to obtain the eagle for a mascot—Perkins granted it. The men of the company pooled their resources to gather $2.50 to purchase the eagle from McCann. Later, a local businessman named Mills Jeffries paid McCann the cost and instructed him to refund the enlisted men’s money. The infantry company had been known as the Eau Claire Badgers, but during their journey to Camp Randall in Madison with their new mascot, they quickly changed their nickname to the Eagles. It was also during this trip that the eagle was named Old Abe, in honor of President Abraham Lincoln.

The Eagle Likes to Dance

Upon reaching Camp Randall, a band’s impromptu performance of “Yankee Doodle” excited Old Abe. He grabbed a corner of one of the flags that were carried on each side of him in his beak and held it while flapping his wings. Local newspapers raved about the incident and cited it as a good omen.

Sticks and Stones and Offers of Cash

At Camp Randall, the Eau Claire men were mustered into federal service as Company C of the Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry Regiment and went through basic training. While on their way to the fighting front, the Eighth passed through St. Louis, where Old Abe was subjected to scattered taunts and jeers of “wild goose” and “Yankee crow” by Southern sympathizers. In this excitement, Old Abe became flustered and broke the tether that secured him to his post. His freedom lasted only a short while as several men in the company broke ranks to recapture their beloved mascot and return him to his shield perch. Even amidst the insults flung at him by some, one person offered $500, and another person, “a valuable farm” to purchase the eagle from the unit.

Old Abe at War

Take Cover

Old Abe saw his share of fighting during his time in service. The first major action the Eighth Wisconsin experienced took place at Farmington (Mississippi) in May 1862. During the battle, Captain Perkins ordered James McGinnis, who carried Old Abe, to the rear for protection. Later in the battle, the regiment took cover from Confederate artillery fire. McGinnis realized that he was out of the range of the artillery and did not lie down with some of the others in the company. Old Abe, imitating the men, leapt down from his perch. Seeing this, McGinnis picked him up off the ground and placed him back on his perch, only to have him jump back off the perch to the ground. After several attempts to get Old Abe to remain on his perch, McGinnis reluctantly joined the mascot, taking cover on the ground. When the regiment rose from cover, Old Abe leapt back on his perch and flapped his wings to convey his readiness.

Mischief on Liberty

While the Eighth was at Camp Clear Creek after the fall of Corinth in late 1862, eagle-bearer Thomas Hill gave Old Abe relative freedom, a rarity in the field. This “liberty” allowed Old Abe to cause a great deal of mischief. Some of his adventures in camp included tipping over fire pails full of water to the frustration of soldiers who had to refill them, chasing large insects that caught his eye through camp, learning to play catch with soldiers as they rolled round bullets along the ground, visiting the sutler’s tent, ambushing freshly laundered clothes left out to dry, and raiding the provisions of various companies within the boundaries of the camp. Old Abe also became drunk on at least two occasions from spirits that soldiers left unattended. Like his brethren in the wild, Old Abe enjoyed any opportunity to be near water. Hill and others often accompanied Old Abe to Clear Creek where he could enjoy the stream.

Always on Alert

Whether on the march, in the field, or at camp, Old Abe remained constantly aware of his surroundings. On at least one occasion, he raised an alarm about a rebel courier while the Eighth was near Bayou Rapide, Louisiana. This alertness even applied to strangers who tried to approach him. It has been documented that Old Abe was not fond of strangers attempting to pet him but appeared to derive happiness from contact with men in uniform. Even years later, men of the Eighth could approach Old Abe without any hesitation about how they would be received by their old friend.

War Ages Eagles, Too

The Eighth’s initial three-year enlistment came to an end in the summer of 1864, and Old Abe joined the reenlisting soldiers on their trip back to Wisconsin for a furlough. Upon returning to the field in late July or early August 1864, the men who had remained at camp almost did not recognize the eagle. Old Abe had achieved maturity, and the white head and tail feathers that came with it, while on furlough. With the original enlistments coming to an end, the men decided that Old Abe, who had also survived three years of war, would not reenlist. They struggled to choose a permanent home for the eagle, with proponents for Eau Claire, Madison, and even Washington, DC. In the end, a unanimous vote from the entire regiment presented Old Abe to state authorities in Madison.

Battle Record for Old Abe with the Eighth Wisconsin

| 1861

Fredericktown, Missouri |

October 21, 1861 |

| 1862

Siege of New Madrid and Island Number 10, Missouri Point Pleasant, Missouri Farmington, Mississippi Before Corinth, Mississippi Iuka, Mississippi Burnside, Mississippi Iuka, Mississippi Corinth, Mississippi Tallahatchie, Mississippi |

March and April 1862 March 20, 1862 May 9, 1862 May 28, 1862 September 12, 1862 September 13, 1862 September 16 and 18, 1862 October 3-4, 1862 December 2, 1862 |

| 1863

Mississippi Springs, Mississippi Jackson, Mississippi Assault on Vicksburg, Mississippi Mechanicsburg, Mississippi Richmond, Louisiana Vicksburg, Mississippi Surrender of Vicksburg, Mississippi Brownsville, Mississippi |

May 13, 1863 May 14, 1863 May 22, 1863 June 4, 1863 June 15, 1863 June 24, 1863 July 4, 1863 October 14, 1863 |

| 1864

Fort Scurry, Louisiana Fort de Russy, Louisiana Henderson’s Hill, Louisiana Grand Ecore, Louisiana Pleasant Hill, Louisiana Nachitoches, Louisiana Kane River, Louisiana Clouterville, Louisiana Crane Hill, Louisiana Bayou Rapide, Louisiana Bayou La Moore, Louisiana Bayou Roberts, Louisiana Moore’s Plantation, Louisiana Mansura, Louisiana Maysville, Louisiana Calhoun’s Plantation, Louisiana Bayou de Glaise, Louisiana Lake Chicot, Louisiana Hurricane Creek, Louisiana |

March 13, 1864 March 15, 1864 March 15, 1864 April 2, 1864 April 8- 9, 1864 April 20, 1864 April 22, 1864 April 23, 1864 April 23, 1864 May 2, 1864 May 3, 1864 May 4-6, 1864 May 8-12, 1864 May 16, 1864 May 17, 1864 May 18, 1864 May 18, 1864 June 6, 1864 August 13, 1864 |

Close Calls for Old Abe

While Old Abe did not shed any blood during the Civil War, there were several close calls. At the Battle of Corinth, a minie ball severed the leather cord connecting the eagle to his perch, setting him loose on the battlefield. Old Abe flew down the Federal lines with eagle-bearer David McLain chasing after him. Upon seeing the famed eagle flying down the enemy lines, many Confederate soldiers attempted to shoot him down. Later, many stories and rumors of his exploits during this battle arose.

Aerial Reconnaissance

Some of Old Abe’s supposed actions during this brief taste of freedom including carrying out “aerial reconnaissance of the Confederated lines, delivering messages for some of the commanding officers in the field, and rallying the Union forces by soaring over them and screaming his famed war cry. One story is believed to hold some basis in fact. It involves Confederate General Sterling Price, who upon seeing Old Abe flying along the Union lines, offered a bounty to his men for the capture of the eagle, dead or alive. According to the story, he stated that Old Abe was worth more to Union morale than a whole brigade or a dozen battle flags.

In reality, Old Abe’s famous flight lasted roughly fifty feet before McLain caught the eagle in his arms and quickly exited the battlefield. Old Abe lost several wing and tail feathers from the incident but escaped otherwise unscathed. Following the battle, his wings were clipped to prevent similar mishaps in the future. McLain resigned his place as eagle-bearer in protest of the procedure.

Don't Look This Way

Old Abe’s other documented close call came while he and the Eighth participated in the Vicksburg campaign. During the siege, a Confederate minie ball traveled down the eagle’s neck and chest, removing the feathers along its path. If the ball had hit at a different angle, or if Old Abe had been facing a slightly different direction, he would have been much more severely wounded and possibly killed. Instead, he merely suffered a wound in the webbing of his left wing, leaving behind a round hole. According to records, neither he nor his eagle-bearers suffered any significant injury while engaged in combat.

The Eagle Bearers

While “eagle bearer” was never an official rank in the Union Army, the Eighth Wisconsin created it as an honorary position. Throughout the Civil War, five men held the unofficial, yet highly sought after, rank of eagle bearer. In addition to the honor of caring for and protecting Old Abe, the eagle bearer was spared guard and fatigue duty.

Gluten-Free Diet

Aside from being a popular target for Confederate sharpshooters, the most difficult aspect of being the eagle bearer may have been attempting to feed Old Abe, a notoriously picky eater. Beef made up the majority of his diet, with the addition of an occasional rabbit or squirrel as they were caught. When beef was unavailable, chicken or duck frequently filled the void. Old Abe refused to eat any kind of grain. Interestingly, eagle-bearer David McLain stated that the eagle was “very fond of minnows,” presumably due to their similarity to the fish that make up a major part of a wild bald eagle’s diet.

Listed below are the five members of the regiment who served as eagle-bearers, with the dates they held the position during the war:

- James McGinnis: September 1, 1861 – May 30, 1982

- Thomas J. Hill: May 30, 1862 – August 18, 1862

- David McLain: August 18, 1862 – October 1862

- Edward Homiston: October 1862 – September 1863

- Jacob Burkhardt: September 1863 – September 1864

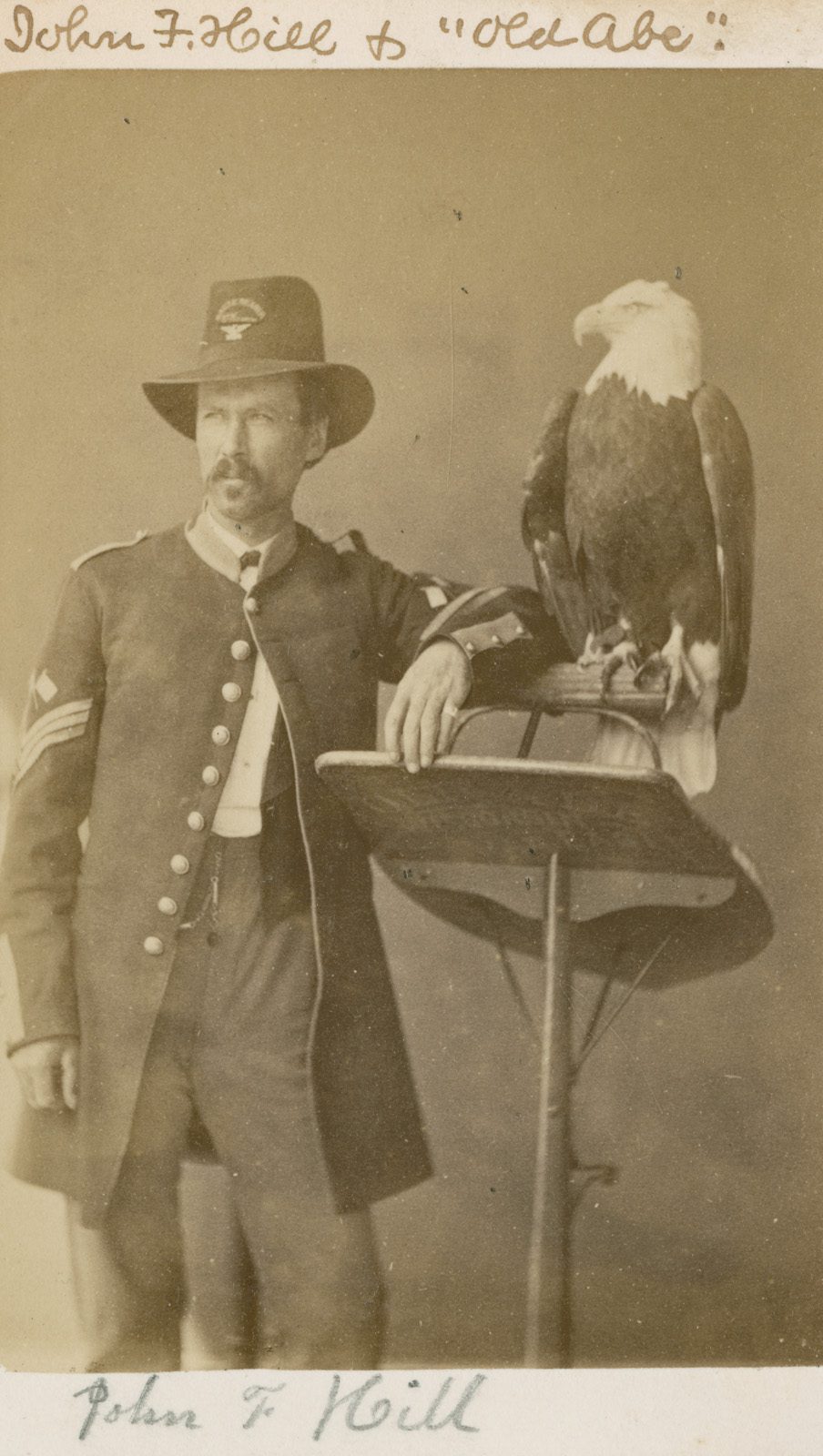

*John F. Hill, brother of Thomas Hill, served as eagle-bearer during the journey from Chicago to Madison in September 1864.

Post-War Life for Old Abe

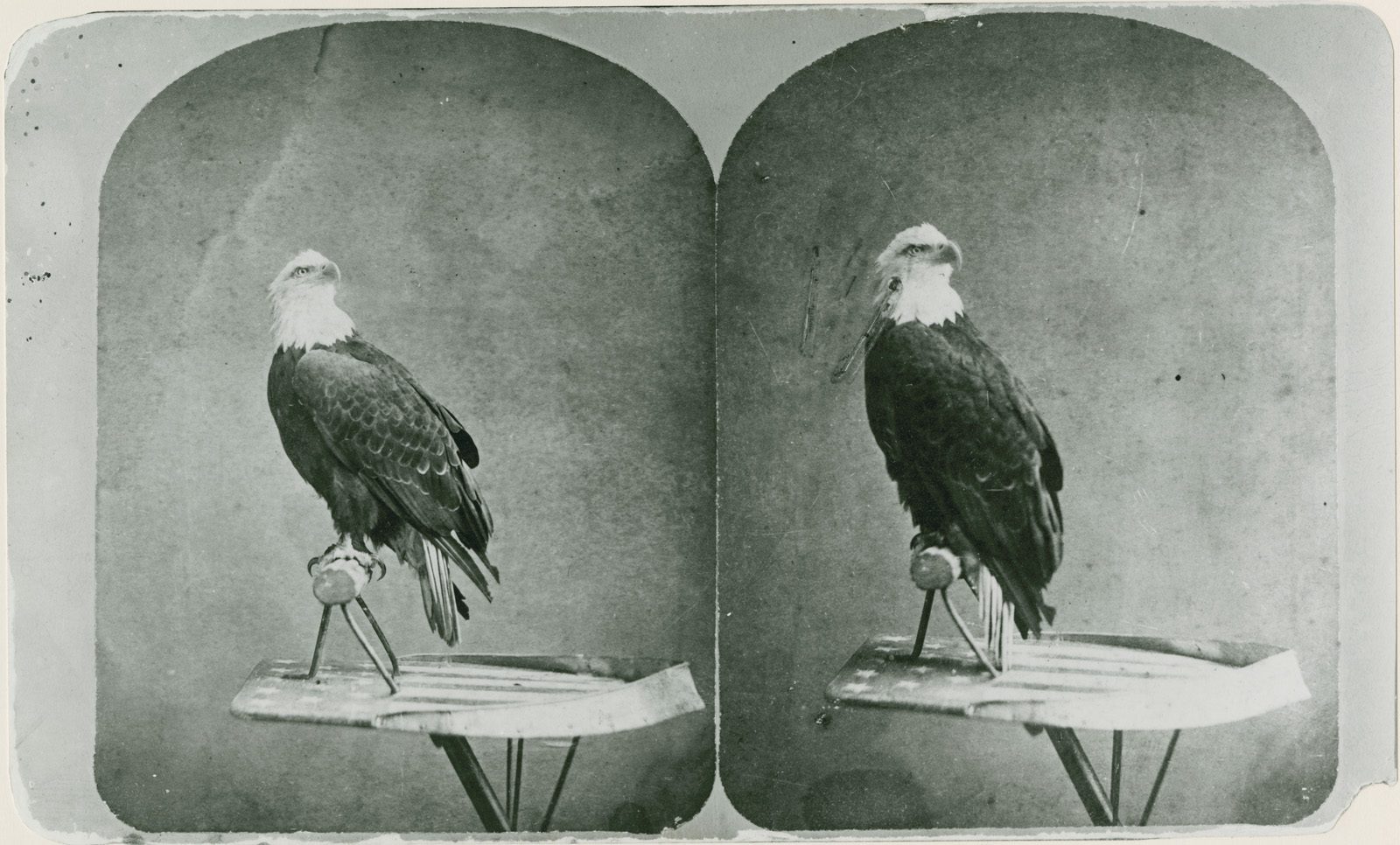

Celebrity Takes Up Residence at the State Capitol Building

In September 1864, the state of Wisconsin took possession of Old Abe and reclassified him as a “War Relic.” A newly created “Eagle Department” in the Capitol building included a caretaker, two room “apartment,” and custom bathtub for Old Abe.

Old Abe became a nationally known celebrity with individuals and organizations from around the state and country requesting his presence at their events. The majority of these events were either reunions of Civil War veterans or fundraisers for various charities, though he did attend larger events like the Philadelphia Centennial in 1876. Some of the charities Old Abe "supported" included the Soldiers' Home Fair, Soldier's Orphan's Home, Harvey Hospital, and the Ladies Aid Society of Chippewa Falls. He also made many appearances at events for Wisconsin Republican candidates, who held control of the state political scene following the Civil War. As happened during the Civil War, offers to purchase Old Abe continued after the war. While at the Northwest Sanitary Fair in Illinois in 1865, a wealthy individual offered 10,000 dollars and P. T. Barnum, the famous circus showman, offered 20,000 dollars.

Old Abe Kills Roommate

In March 1866, a roommate joined Old Abe in "The Eagle Department." The Forty-Ninth Wisconsin Infantry Regiment, during its seven months of service in the war, acquired a golden eagle named Timothy, whose name was later changed to Phil Sheridan, and finally to Andy Johnson. He joined Old Abe in the Capitol, though he was not tame and did not attend any public appearances. In fact, the two eagles became bitter rivals and fought on numerous occasions, with Andy Johnson wounding Old Abe at least once. Late in 1873, Old Abe attacked Andy Johnson, catching him off-guard, and sinking his talons deep into the neck of his rival. Andy Johnson died the following spring, due in part to the wounds Old Abe inflicted. Ironically, Andy Johnson was taxidermied and later occupied a place alongside Old Abe in G.A.R. Memorial Hall.

Old Abe Dies

A small fire broke out in the basement of the Capitol in February 1881. After Old Abe raised an alarm, the fire was put out quickly. However, the eagle inhaled a large amount of thick black smoke, which had an immediate negative impact on his health. About a month later, on March 20, 1881, Old Abe began refusing food. He visibly lost strength and continued to decline in spite of the care and attention of numerous doctors. On March 25, he began experiencing spasms and the next day, March 26, 1881, Old Abe died in the arms of his final caretaker George Gilles.

Following his death, veterans from all over Wisconsin volunteered to serve as pallbearers at Old Abe’s funeral. A debate also arose over the ultimate disposition of his remains. Many championed Union Rest at Madison’s Forest Hill Cemetery as the appropriate location for burial. Even after Governor William E. Smith decided on taxidermy to allow future generations to see the legendary bird, debate continued over where the mounted eagle should be displayed. Smith ultimately chose the Capitol building and placed Old Abe’s remains on display in a glass case located in the rotunda on September 17, 1881. Interestingly, many visitors commented that the rendering lacked a life-like appearance.

Famous in Death

Just four years later, Old Abe was moved from the rotunda to the G.A.R. Memorial Hall, also located in the Capitol. In 1900, his remains were transferred to the new State Historical Society of Wisconsin building on the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus. However, pressure from veterans convinced Governor Robert M. Lafollette to return Old Abe to the Capitol building in 1903. During a visit that same year, President Theodore Roosevelt stopped at the Hall to view Old Abe’s remains and expressed his pleasure at being able to view the eagle he had studied in school as a child. Tragically, less than one year after this last move, Old Abe’s remains and glass case were destroyed in a 1904 fire that also razed the entire Capitol building.

“Eagle Department” Caretakers

- John McFarland: State Armorer

- Angus R. McDonald: State Armorer, Eleventh Wisconsin Infantry

- John G. Stock: State Armorer, Fourth Wisconsin Cavalry

- G. Linderman: State Armorer, Fifth Wisconsin Infantry

- William J. Jones: Sixteenth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

- George W. Baker: Nineteenth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

- E. Troan: Civilian

- John F. Hill: Eighth Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

- Peter B. Field: Civilian

- Mark Smith: Seventh Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

- George Gilles: Second Wisconsin Volunteer Infantry

The Legacy of Old Abe

Old Abe's legacy began while he was still alive. From his triumphant arrival at Camp Randall, through his brief flight at Corinth, to his post-war "celebrity" appearances at state and national functions, he captured the imagination and affection of people in Wisconsin and around the country. Following his death in 1881, he and his story quickly became legend and Old Abe himself became a symbol of the Civil War, the state of Wisconsin, and ideals like patriotism and bravery. This becomes evident when considering the wide array of places and ways that Old Abe's likeness has been used around the country, and the places it continues to be used to this day.

Vicksburg Monument

Old Abe’s strong association with the Civil War and Wisconsin veterans is reflected on numerous monuments across the country. One example is the Wisconsin monument at Vicksburg, Mississippi, where Old Abe and the Eighth Wisconsin saw action. The forty-seven-and-a-half-foot granite column is topped by a six-foot bronze statue of Old Abe. An image of Old Abe is also carved into one side of the Eighth Wisconsin Monument at Vicksburg. Closer to home, the Camp Randall Memorial Arch is located on the grounds in Madison that held the Civil War training camp in the 1860s and holds a college football stadium today. Dedicated in 1912, the Arch honors all Wisconsin Civil War veterans and features a stone statue of Old Abe perched on top.

J.I. Case & Company

Four years after the Civil War, J.I. Case & Company founder Jerome Increase Case began using Old Abe’s likeness for his company’s emblem. The eagle, first appearing on the Case Eclipse Thresher in 1869, remained the company’s symbol for 100 years. The first logo pictured a likeness of Old Abe on a branch with the words, “J.I. Case Threshing Machine Co.” and the company’s home, Racine, Wisconsin, printed on the branch itself. Years later, conveying a more global approach, the company decided to portray the likeness on top of a globe with the same words on the face of the globe. This new logo appeared in advertisements for the company, as well as on the sides of many of its machines and as hood ornaments. Cast iron statues of the logo were placed at Case facilities around the world. In 1969, the company decided to revamp their corporate logo and ceased using Old Abe.

101st Airborne Division

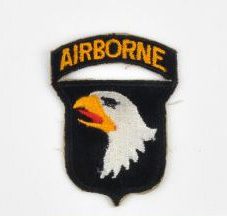

The shoulder patch for the famous 101st Airborne Division also features Old Abe. Organized for World War I, the 101st was reorganized in 1921 with its headquarters in Milwaukee. The men surely heard stories of Old Abe, as the unit quickly adopted an insignia with a white eagle above flames on a royal blue shield. Later the flames were removed and the blue shield was replaced by a black shield. The “Airborne” tab now seen above the shield was added in 1942. During World War II, the 101st received its first of two eagle mascots. Named Young Abe, the eagle was captured in Wisconsin and presented to the 101st by the State in November 1942. However, Young Abe died less than one year later. Bill Lee I, the division’s second eagle mascot, was acquired in September 1956 and named after the division’s first commanding officer, Major General William C. Lee. Bill Lee, too, died less than one year after joining the 101st.

Old Abe Today

Many high schools have mascots with a local connection or special meaning to the community. Eau Claire Memorial High School chose the “Old Abes” to honor the famous military mascot whose military journey started in their city. The school also has an Old Abe Memorial Garden located in its courtyard. Many other area businesses and attractions have been named after Old Abe, including a state trail, photo studios, and a supper club in the area where the McCann’s home once stood.

Wisconsin continues to honor Old Abe to this day, with mounted eagles representing Old Abe featured prominently on the arch at Camp Randall and in two state buildings: the Assembly Chamber in the State Capitol and the 19th Century Gallery of the Wisconsin Veterans Museum (WVM). In addition, the WVM preserves a substantial Old Abe manuscript collection featuring original papers and photographs relating to this unique figure in U.S. history which are featured in this article.

Learn more by reading Old Abe the War Eagle: A True Story of the Civil War and Reconstruction by Richard Zeitlin. The books is available in WVM's gift shop.