At the Outbreak of War: Army Nursing Corps

During World War I, the entire nation was mobilized for service. As in the Civil War and other previous conflicts, women answered the call by volunteering as nurses. This exhibit concerns itself with two people and one unit with Wisconsin ties. Helen Bulovsky was born in Madison in 1895, of immigrant parents. She trained at Madison General Hospital, and after her graduation in October of 1917 practiced as a registered nurse. Bulovsky had a heart defect, which it seems she was aware of at the point of her enlistment in April 1918. She was assigned to Base Hospital 22. Base Hospital 22 was formed at Knowlton Hospital in Milwaukee. The doctors became officers, but nurses were not given military ranks at this time. The staff was then supplemented with soldiers from regular Army sanitation units. Aimee O’Keefe was born on a small farm in St. Croix County in 1889. She trained as a nurse in St. Paul, Minnesota. After being certified she practiced in Los Angeles, California; Lewiston, Montana; and Seattle, Washington. O’Keefe was called to active duty in April, 1917. She was assigned to Base Hospital 50, organized through the University of Washington Hospital.

As of the declaration of war on April 16, 1917 the Army Nursing Corps consisted of a mere 235 regulars and 165 reserve members. By the end of the war, the ranks of the Nursing Corps would swell to 21,480. The U.S. Army made the decision to employ sanitary personnel at a rate of 7.65%, lower than the recommended 10% of total troop strength. By these calculations, this number of nurses was adequate for an army of 1,000,000 men. The U.S. drafted 4,000,000 men, creating a serious shortage of medical personnel.

Short on Food, Long on Work at Base Hospital 22

“Last night they operated on sixty five. So you see we are busy. I have charge of several tents and it keeps me busy. There isn’t much we can do for the boys here except keep their dressings clean keep them warm and give them hypodermics.” - Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her parents, August 7th, 1918.

After a brief stint at Camp Merritt, New Jersey, the main training base for medical personnel in the United States, the nurses traveled to New York harbor, where they boarded ships for France. Bulovsky arrived in France on June 22, 1918. She transferred from Base Hospital 22 to Evacuation Hospital 5 a month later. This move put her as close to the front as a nurse could get.

Prior to the war, thought had been given to the medical requirements of units in combat. Standard Army organization provided for 2 evacuation hospitals per division. Each hospital was to have 432 beds. This was a short lived standard however. Drawing on lessons of the French and British armies, the new organization required a minimum of 1,000 beds per evacuation.

The Army never met this standard. Of 42 divisions (29 in combat), there were only 37 Evacuation Hospitals (22 in combat), well under the authorized strength.2 This meant that Evacuation Hospitals were under tremendous strain, often operating at or above their listed capacity. Bulovsky’s Evacuation Hospital No. 5 handled 15,195 patients between September 15, 1918 and the end of the war on November 11, 1918.

At the base hospitals, conditions were not much better. There was one base hospital per division, which was adequate according to organizational charts. These base hospitals were mostly Red Cross units, in other words city hospitals which were activated during the war. For example, Base Hospital 22 was comprised of staff from Knowlton Hospital in Milwaukee, and Aimee O’Keefe’s unit, Base Hospital 50, was organized in Seattle, through the University of Washington. Out of 42 total Base Hospitals, 36 were formed in this way. Base Hospital 22 handled over 17,000 patients between July 25, 1918 and January 25, 1919.

Nurses had many daily tasks. The wards had to be cleaned, dressings changed, soldiers given medicine, and instruments sterilized, just to name the more obvious tasks. Personal hygiene was also important in such an environment. Lice and fleas could spread diseases like yellow fever and were a constant threat.

The fall and winter in France and Belgium are quite rainy, and mud was a constant annoyance. In Bulovsky’s case, the nurses were housed in tents which lacked floorboards. In Base Hospitals the situation was a little better. All buildings and tents had floors, usually of wood, however, the walk from one’s quarters to the mess or the wards was a burdensome trudge.

“We are short of food here. The last I weighed 94 lbs. but it will be 84 before long. One of the girls at our base died.” - Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her parents, November 9th, 1918.

“You put up plenty of jam and have plenty of fat for pies and we will have cake every meal. Oh, just one square meal again like you always cook…I expect you wonder why I am raving so about eats. Well, we had beans for supper and fish. Do you wonder that I’m hungry?” - Aimee O’Keefe Kinney in a letter to her mother, December 19, 1918.

“[W]e had no diner on the train we had to take our rations with us which consisted chiefly of corn-wooly, wolly beef, bread and butter. Several times we got hot coffee at a station, and water was a real treat.” - Aimee O’Keefe Kinney in a letter to her sister, September 17, 1918. She was on her way to the front.

Food, a constant complaint of soldiers, was a complaint of the nurses as well. The most prevalent item was “bully beef”, corned beef tinned for preservation. Beans, due to their low price and high protein content, were another staple. O’Keefe related that though they had white bread, they almost never had potatoes, and sweets were a rarity. Sometimes, nurses could scrape some resources together and throw a “fudge party” and make a batch of the sweet treat.

Casualties

The First World War saw some of the worst wounds imaginable. In particular, artillery and gas caused horrendous damage to soldier’s bodies, and often their minds. When a soldier was injured, first he would be given first aid and then removed from the front line. The soldier was then sent to the battalion aid post. At the battalion aid post, the casualties were given an anti-tetanus shot and a diagnosis tag, and sent on to the nearest ambulance dressing station. At this location, first aid and shots were given to those who had not previously received such treatment, and the casualties were then transported to Evacuation Hospitals.

“Madison certainly must be a blue place now that they are notified of the mortalities. We all sympathize with them but the Lord knows we are doing all there is. …The most pathetic thing I hurry against is when the boys wake up from ether and find that an arm or leg has been amputated but like soldiers they bear it bravely.” – Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her parents, October 16-18, 1918.

At an Evacuation Hospital, like where Helen Bulovsky worked, the goal was to cycle patients through within 24 hours. This often only happened with the least severe cases, such as broken bones and flesh wounds. Often these less serious cases were given minimal treatment, typically only going to the admission, dressing and shock wards. The shock ward, which is where Bulovsky worked most of the time, was a tent kept at 90 degrees Fahrenheit. The nurses there kept the patients warm with blankets and hot liquid. They also administered shots to fight infection or dull pain, and changed dressings. More serious cases, such as brain trauma, spinal trauma and shattered femurs were operated on at the Evacuation Hospital, with the most serious cases given priority. It was not uncommon that about 25% of casualties were serious enough to require surgery in the Evacuation Hospital. These cases were kept at the Evacuation Hospital until they were stable enough to be transported to a Base Hospital.

“We are in the biggest hospital center in the world. They say there are about twenty-five thousand patients here…” – Aimee O’Keefe Kinney in a letter to her sister, November 24, 1918.

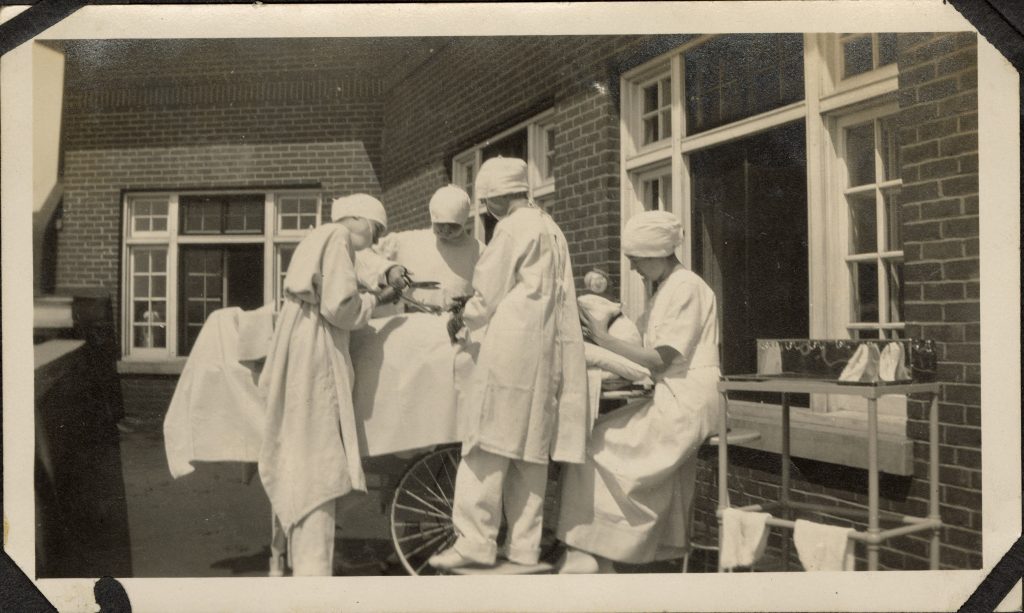

At the Base Hospital the level of care, and term of stay, increased dramatically. The wards were buildings, only supplemented with tents if capacity was exceeded. Surgery could be performed in a much more sterile and controlled environment. The Base Hospital was located in the several miles behind the front, where artillery did not present a great danger. Base Hospitals formed the backbone of the medical core, totaling 42 units by the war’s end. Base Hospitals became huge by war’s end, often housing over 5,000 patients.

Illness at Base Hospital 22

“It has been so cold that I walk around with my coat all the time. So many of our girls are getting sick, something like grippe and I try to dodge it. Miss Mathews is trying to get us back to the base so we can rest and send another group out.” – Helen Bulovsky, September 27th, 1918

Some nurses died during service, usually of illnesses such as influenza. Nurse Florence Kimball died on October 21st, 1918 and was buried in the military cemetery at Base Hospital 22. She was 24 years old.

At the end of the war, there was a global epidemic, the Spanish Influenza of 1918. Nurses were especially at risk because they were overworked, under fed, and exposed to sick troops in their wards. In the case of nurses working at evacuation hospitals, like Helen Bulovsky, the situation was made worse by shortages of clothes, stoves, and constant rains. Typhus, diphtheria, pneumonia, and bronchitis were all very real health hazards to the Nursing Corps and claimed many lives even after the war was over.

“I am in bed with everything imaginable on, even a muffler around my neck. I have had another attack of quincy….The first 3 days my throat was swollen. I remained on duty. Outside my throat felt fine and the boys need every little bit of our attention available. By night I couldn’t talk so I had to go to bed.” – Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her parents, October 8th, 1918.

The Holidays Overseas

Despite the fact that the war ended on November 11, 1917, the holidays were not as joyous as they could have been for most. Thanksgiving and Christmas were spent in France, far away from loved ones. The nurses made due with what they could. They decorated their quarters, the mess and the wards. They served meals to the patients. Holiday parties were thrown. Bulovsky and her friends sang carols in the wards. Despite the hardships and tears, Bulovsky still wrote her father that it was the best Christmas ever.

"Our turkey was not like the one you used to cook. I wonder if the Boss is giving his usual Thanksgiving Banquet today?" – Aimee O'Keefe Kinney in a letter to her sister, November 28, 1918.

“This is 7:30pm Xmas eve and I have just finished crying… Well I can’t seem to finish this. Mother it is just awful to be away from home. This is my first Xmas away from home and it hurts.” – Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her mother, December 24, 1918.

“Today a bunch got newspapers and they think the war will end in a couple of weeks. It certainly won’t end any too soon to suit me.” – Helen Bulovsky in a letter to her parents, November 9th, 1918. The war ended on November 11th, 1918, a mere two days later.

The war ended officially at 11:00 a.m., November 11, 1918. As could be expected, everyone was thrilled by the prospect of going home. However, most had to suffer through the winter months in Europe before leaving for home. There were many troops to care for who were seriously wounded, and required more recovery before they could safely be transported.

There also was the Spanish Flu epidemic, which created more patients to care for, sometimes the nurses themselves among them. Not least of all, there was a shortage in transportation. It took several months to ship all the soldiers and nurses to France; there were too many people for the transport ships to bring them all back at once.

Coming Home

“But when I do come home, I’m just going to talk, eat, and sleep for one whole year.” – Aimee O’Keefe Kinney in a letter to her mother, December 19, 1918.

Aimee O’Keefe’s case a typical example. O’Keefe set sail on April 13, arrived at Hoboken on April 23, was discharged and allowed to proceed home on April 29 and formally discharged and issued her final paycheck and bonus on June 1.

Aimee O’Keefe married Robert Kinney a year later. They had six children together. Aimee O’Keefe Kinney became the commander of the Otis H. King American Legion Post in Hudson, Wisconsin in 1936. She was the first woman to become a post commander in this state, and later became a county commander.

Helen Bulovsky returned to Madison on March 15, 1919. In 1922 she married Walter Lawrence, but died nine months later, on February 16, 1923.

Base Hospital No. 22’s doctors and nurses returned home to their practices. By the end of the war, the hospital was the largest in size, and ranked third in quality out of the entire American Expeditionary Force.

The services provided by Helen Bulovsky, Aimee O’Keefe Kinney, and the staff of Base Hospital 22 were invaluable to the success of the war effort, and vital to the many soldiers they treated. It is no stretch to say their time in France, though difficult, was among the proudest and most fulfilling of their lives.

Bibliography

Bulovsky, Helen C., 1895-1923. Papers and Photographs, 1914-2001. WVM Mss 536

Kinney, Aimee O’Keefe, 1889-1959. Papers and Photographs, 1909-2004 (bulk 1918-1919). WVM Mss 421

United States. Army. Base Hospital 22. Records and Photographs, 1918-1976. WVM Mss 500

United States. Surgeon General’s Office. The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War/Prepared under the direction of M. W. Ireland by Charles Lynch.: G.P.O.,: 1923-1929.

Related Resources

Beffel, John M. Papers and Photographs, 1891-1942; (bulk 1917-1918). WVM Mss 503.

Official Committee of Base Hospital Fifty. The History of Base Hospital Fifty: A Portrayal of the Work Done by this Unit while Serving in the United States and with the American Expeditionary Forces in France. Official Committee of Base Hospital Fifty. 1922.

Saltonstall, Nora with Judith S. Graham, ed. “Out Here At the Front”: The World War I Letters of Nora Saltonstall. Northeastern University Press: c 2004.

Shay, Michael E. A Grateful Heart: The History of a World War I Field Hospital. Greenwood Press: 2002.

Strott, George George. The Medical Department of the United States Navy with the Army and Marine Corps in France in World War I: Its Functions and Employment. Navmed 1197. Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, U.S. Navy Dept. 1947.

Surgeon General’s Office. The Medical Department of the United States Army…157-8. United States.

Surgeon General’s Office. The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War/Prepared under the direction of M. W. Ireland by Charles Lynch.: G.P.O., 1923-1929. Vol. I, 315.